Idomeni, at the border between northern Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), has become one of the symbols of the huge refugee movement of 2015 and 2016.

Thousands of children, women and men – on foot, loaded with bags, some pushing wheelchairs carrying loved ones – passed here as they tried to make their way to the safety of northern Europe. Then Hungary closed its borders, and like a row of dominos, other countries followed.

Macedonia closed its border on 9 March 2016. Suddenly Greece found itself with thousands of refugees at its borders, enduring wind, rain, snow and heat in the hope the border would soon re-open. It never did.

Between 24 and 26 May 2016, the makeshift camp at Idomeni was eventually evacuated by the Greek police. Journalists Isabelle Merminod and Tim Baster were there to bear witness.

27 April 2016, Isabelle Merminod

The refugees at Idomeni were mainly from war-torn Syria but they come also from Iraq, Afghanistan, the Maghreb and parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Most had taken decrepit boats or inflatable dinghies to cross the few kilometres from Turkey to the Greek islands. On arrival in Greece, they got a pass allowing them to cross the Greek mainland to northern European countries. But once the border was closed, they found themselves stuck.

22 May 2016, Isabelle Merminod

There were children everywhere in Idomeni camp. A number of ‘Idomeni babies’ were born. Some small children remained close to the safety of the legs of their parents. The more daring ones played, sometimes in less safe areas of the camp, to fight off the boredom of waiting for the border to reopen. Some stayed at Idomeni camp for nearly three months. The UN refugee agency UNHCR says that some 38 per cent of refugee arrivals into Greece are children.

26 May 2016, Isabelle Merminod

At its height, Idomeni had an estimated population of some 14,000 people, many of them families, with up to 2,000 children. Volunteers from all over the world worked with the refugees to help educate the children in subjects including mathematics, Arabic, Kurdish and English. One refugee teacher expressed his shock that some of the kids – missing years of schooling due to the war in Syria – could not even read or write their own language.

20 April 2016, Isabelle Merminod

Hoping that the gates into Macedonia would re-open, refugees dug into this patch of land. They were unable to register an application for asylum with Greece, nor register for relocation into Europe as the process was only carried out through a Skype address, which rarely responded. With hope dwindling each day, entire families clung to their shelters through the wind, rain, heat and dust of northern Greece until the final evacuation of 24 to 26 May 2016. The ones who set up their tents at Idomeni train station were protected from the mud but would had been the last to cross had the border re-opened. It didn’t.

22 May 2016, Isabelle Merminod

Two days before the evacuation, volunteer clowns played a last show in front of an audience of children and adults delighted to have minds transported away - even if only fleetingly - from their uncertain future. Volunteers at Idomeni included doctors, nurses, mechanics, fire fighters, technical experts running satellite telephones and people with no special skills but plenty of empathy. Some of the volunteers, who came from all over the world, took annual leave to distribute food and clothes, treat kids in the free clinics, play with them and teach them. All contributed to the, occasionally chaotic, running of camp.

26 May 2016, Isabelle Merminod

The evacuation at Idomeni was free of violence. Journalists and volunteers were forced out of the camp by plainclothes police officers and the camp itself was bulldozed flat. The refugees were then bussed by the army and police to official camps, mostly 80 kilometres away, near Greece’s second city of Thessaloniki. A 24 year-old Syrian man said: “When in the morning you open your tent and you see police boots in front of your door, you do not have other choice to pack your stuff and go”.

23 May 2016, Isabelle Merminod

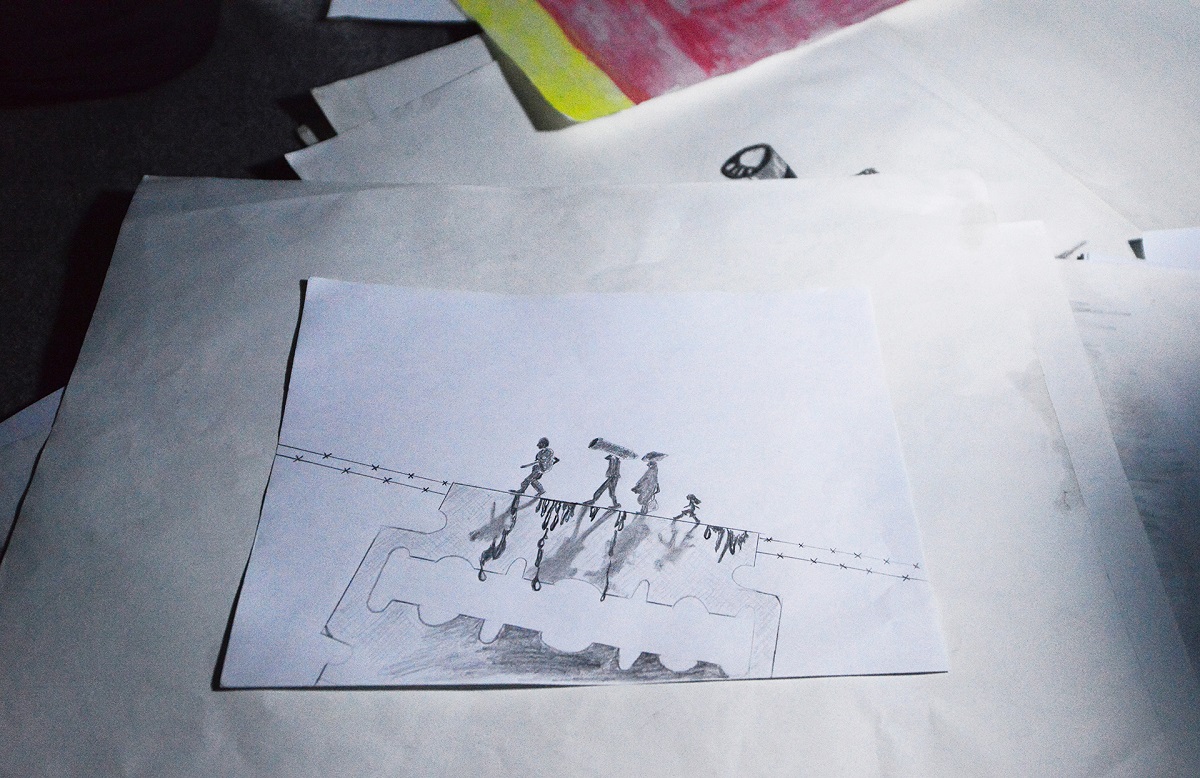

On the eve of the Idomeni evacuation, an Iranian refugee and camp veteran Helal, showed his drawings. ‘Balancing on a razor edge’ maybe illustrates being trapped in Idomeni, running out of money, facing smugglers asking between €800 and €2,000 for the trip to Serbia, and feeling your hope drain away.

23 May 2016, Isabelle Merminod

For weeks before the evacuation, refugees were invited to leave and buses were made available. However, some refugees were worried about going to other camps. They had heard that communications were not good and they feared that if journalists were not able to enter, that they would be forgotten. But as the deadline approached for Idomeni’s closure, many people went to official camps ‘willingly’.

26 May 2016, Isabelle Merminod

In Kalochori camp, just outside of Thessaloniki, a huge warehouse guarded by police houses over 100 tents holding almost 500 refugees. Despite being fenced off, it appears the camp’s inhabitants can come and go as they wish for the moment, but journalists are refused entry. Recently, the Greek government started to register all the people in the official camps who arrived before 20 March 2016. Registration – the first step to relocation in northern Europe – had started. Hope was reborn.

26 May 2016, Isabelle Merminod

UNHCR has expressed concern about the conditions in some of the camps, which like this one called Sindos, were often converted warehouses with fairly basic facilities.

In September 2015, the EU promised to relocate 66,400 refugees out of Greece by September 2017. By 7 June 2016, only 1,281 refugees had been relocated. Greece has a population of some 10 million people and the EU has a total population of over 500 million. UNHCR says that Greece is looking after some 46,000 people on its mainland. Will Europe ever honour its promise to relocate them?