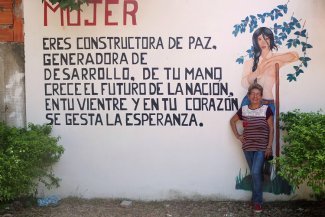

Around 487 trade union organisations have affected by violence in Colombia, and the phenomenon persists. In this February 2021 image from Bogotá’s Museum for Life, urban art and memory are linked. The graffiti commemorates the victims of violence: social leaders, peace signatories and young victims of the military and national police murdered in recent months.

Colombia continues to be “the deadliest country for workers and unionists”, with 22 murders between April 2020 and March 2021, according to the International Trade Union Confederation’s (ITUC) latest Global Rights Index. The overall number of human rights violations targeting the labour movement has fallen in comparison to the most brutal years of the conflict, but even the peace agreement signed five years ago has not brought an end to the violence.

“Most of these crimes remained unresolved, as the government failed to allocate the necessary means for the timely investigation and prosecution of the cases,” says the ITUC report. In addition to these direct acts of violence, “employers regularly violated workers’ right to form unions and got rid of workers’ representatives through targeted dismissals and non-renewal of contracts”.

The Human Rights Information System of the National Trade Union School (ENS) recorded 15,430 violations of trade unionists’ rights to life, freedom and integrity in Colombia between 1 January 1971 and 29 September 2021. Around a fifth of the cases reported were murders: 3,288 trade unionists have been assassinated over the last five decades in Colombia.

The threats linked to trade union work in Colombia are so constant that those involved have grown accustomed to them. Darwin Duque, national vice president of the public health workers’ union Anthoc, recalls the time when he was involved in collective bargaining at the hospital in Roldanillo, in the south-western department of Valle del Cauca, in 2013 or 2014. “That day, in the middle of the negotiations, a parcel arrived containing threats saying that we were not welcome there and that heads would roll if we didn’t leave,” he tells Equal Times.

Two weeks before receiving the threat, he had noticed that the security vehicle he was using at the time was being followed. His name has subsequently appeared in collective threats issued via communiqués or text messages. Such threats have become part of everyday life for Duque and many other trade union leaders. “When I talk to colleagues who have suffered threats, it’s clear that the issue of safety is not taken seriously,” he says.

In 2019 the state withdrew the security it had assigned to him: an armoured vehicle and two bodyguards. They left him a personal security guard, but as Darwin has a motorbike rather than a car, his escort was not able to travel alongside him because “it’s not allowed”.

Marta Alfonso, a teacher and second vice president of the Colombian education workers’ federation, Fecode, also talks of the normalisation of anti-union hostility. “We don’t always even realise we are victims,” says the union leader, who is in charge of monitoring the human rights situation within the union.

Alfonso tells of how she was contacted, earlier this year, by someone wanting to interview a female trade unionist who had been a victim of threats. She started looking through her contacts, until they clarified: “No, it is you we want to talk to. You are listed in the register of women under threat.” The long inventory of threats she has accumulated over 15 years as a trade unionist had gone almost unheeded: “It’s so commonplace that we come to consider being threatened for being a trade unionist as part of the job.”

Threats are the most common type of human rights violation suffered by trade unionists in Colombia’s recent history. The ENS has registered 7,598 cases of threats, representing 49.2 per cent of all the violations of the right to life, freedom and integrity targeting trade unionists: 75 per cent are levelled against men and 25 per cent are against women.

Violence against trade unionists in Colombia is “a systematic, selective and historical phenomenon”, states the ENS in its most recent human rights report Cuaderno de Derechos Humanos. Although marked by more than half a century of armed conflict in the country, this organisation considers that the scope of the violence does not end there, “but is also expressed through its own distinctive rationale, patterns, dynamics and features”.

As a result, during the five decades of conflict and post-conflict – in addition to the threats and murders – 1,954 forced displacements, 783 arbitrary detentions, 740 cases of harassment, 431 attacks, 253 forced disappearances, 196 kidnappings, 110 cases of torture and 74 illegal raids linked to trade union activity were also recorded.

The dynamics behind these trade union rights violations range from the armed actors’ fight for territorial control, counter-insurgent social rhetoric and the ‘ideological correction’ exercised mainly by guerrillas, to the suppression of labour disputes and the desire to exert social and political control over the trade union movement.

The paradox is that the prevalence of the numbers has neutralised any public discussion regarding their gravity. “Social recognition of the phenomenon, political recognition, truth and historical memory are still a work in progress,” says sociologist Viviana Colorado, a member of the ENS rights advocacy department. The coverage given by the majority of the mass media has its share of responsibility, Colorado goes on to explain, both in terms of the failure to record and monitor such incidents and the approach taken when they are recorded, with the victims’ trade union identity often being omitted.

Memory and justice

“Around 487 trade union organisations have been the targets of violence in Colombia,” says Viviana Colorado. The peace agreement between the government of former president Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, formerly Colombia’s largest rebel group) has established a transitional justice system which, according to the researcher, has opened a window of opportunity for the Colombian trade union movement to “move forward with the task of securing recognition of these acts and clarification of the facts, to set precedents enabling us to overcome anti-union violence and the impunity surrounding these types of crimes”, which covers more than 90 per cent of cases, she explains. The approach of the unions has been clearly based on this principle: “We are not talking about a thing of the past, but a phenomenon that remains ongoing,” says Colorado.

The ENS has supported this task by compiling reports from several of the main union organisations for submission to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), mainly to the Commission for the Clarification of the Truth (CEV), an extrajudicial body mandated to compile a comprehensive report on the armed conflict within three years (2019-2021).

Thirteen reports were submitted to the CEV in August 2020. They will serve as inputs for the CEV’s general report on the armed conflict, due in mid-2022, and in which the trade unions hope to be duly represented. So far, according to the CEV’s response to Equal Times, the Commission has received a total of 72 reports covering acts of violence against trade unionists or trade union organisations: six forwarded by the JEP and 66 submitted directly.

According to the ENS, around 90 per cent of the violations targeting labour activism were directed at CUT Colombia (the Central Union of Workers) and its affiliates. The union centre presented a report covering around 3,000 murders of its members.

Francisco Maltés, president of the CUT, says they not only hope that individual reparations will be made to the families but also collective reparations “because the government has to accept and develop a policy to ensure reparation for what has been lost as a result of the assassination of trade union leaders”. The process of collective redress is still in its very early stages.

The country’s two other trade union centres, the CTC (the Confederation of Workers of Colombia) and the CGT (the General Confederation of Workers), have also submitted reports. Separate reports were also submitted by Anthoc, on violations against health workers, Sintraunicol, on those targeting public university workers, the oil workers’ union USO, on violations against its members, Fecode, on the persecution of teachers, Sintraofan, a public employees union in Antioquia on the extrajudicial executions of its members, as well as a joint report on violence against women trade unionists by three trade union centres (CUT, CGT and CTC) and Fecode, and a more general and explanatory report submitted by the ENS.

Among the findings presented in this documentation is the fact that, in most cases, the perpetrators of the violence have not been identified. “For the rest, the main perpetrators were paramilitaries and state bodies. The guerrillas and employers also figure on the list,” according to the organisations’ reports. The unions’ participation in the transitional justice system is also an appeal to the judicial institutions to fill the gaps that result in impunity and to help build the historical memory of poorly documented events such as forced displacement, exile and the virtual disappearance of entire trade unions.

Arturo Rincón Sarmiento, an employee of Indupalma (one of the country’s largest palm oil extraction companies) and vice president of the Sintraproaceites (the Indupalma’s workers’ union) branch in the northern municipality of San Alberto, in Cesar, explains that when they began to hold meetings to prepare the report for the CEV on the impact on workers in the palm oil sector, “some colleagues stayed away because they feared the naming of Juancho Prada [former paramilitary leader] and the Central Bolívar Bloc [a paramilitary organisation], given their continued presence in the region”.

Although the role of paramilitary groups in the persecution of hundreds of trade unionists in the department of Cesar has been proven in court, and there is much less violence now than in the past, the fear is still present, according to Rincón. In addition, Sintraproaceites has been decimated by the voluntary liquidation of the Indupalma palm oil company, with the majority of employees resigning voluntarily on the basis of ‘deals’. Rincón says that, in the 1980s, there were around 2,000 workers at the company. Today there are 72 left fighting to keep their direct contracts rather than being hired through a third party.

According to the most recent ENS report, around 15.7 per cent of the trade union rights violations registered have been in rural sectors such as agriculture, hunting and fishing.

A report submitted to the transitional justice system that testifies to this is that of agricultural union federation Fensuagro, founded in 1976. It states that the regions where they were hardest hit by the violence were the Caribbean region, Magdalena Medio, Urabá in Antioquia – where the federation was “practically exterminated” – and the department of Meta.

The report documents 572 assassinations, “403 of which were allegedly carried out by paramilitary groups and another 107 by state agents”, making Fensuagro “one of the agrarian trade unions with the highest number of members murdered in its history”. And this dynamic has not ceased with the signing of the peace agreement, with rural sectors being the hardest hit by the reconfiguration of armed groups.

Despite the seriousness and the magnitude of these crimes, the state has difficulty recognising them as anti-union violence, having decided, since 2014, to classify them as ‘violence against campesinos [peasant farmers]’ rather than ‘violence against trade unionists’, explains Viviana Colorado. The same is true for teachers, as the violence perpetrated against them is not deemed to be linked to their trade union status but, rather, to the exercise of their profession. This is one of the factors behind the decline in the rate of anti-union violence over the last decade, in addition to the decrease in its intensity relative to previous decades.

According to the records of the ENS, there were 1,518 murders between 1990 and 1999. In the following decade there were 1,045 and from 2010 to 2019 another 283. “Even a single case should be cause for concern,” says Colorado, who also warns of underreporting, as teachers, who are no longer counted, have historically accounted for 45.6 per cent of these acts of violence and, not only are they no longer included but the pandemic has also created problems in the documentation of the cases on the ground.

The case of teachers is also an illustration of the difficulties involved in building memory in the midst of the ongoing violence. In 2019, Fecode submitted the report La Vida por Educar (Life and Limb for Teaching) to the JEP, documenting the cases of violence against unionised teachers between 1986 and 2010. “There were several murders and threats that year [2019]. A rector was killed while we were gathered for a national meeting. We decided to organise a march for life, and we were threatened by the famous Águilas Negras [Black Eagles],” says Alfonso of Fecode. This group, the existence of which the state denies, regularly issues threats to social leaders. In December, Fecode received another threat. Among the ‘grounds’ was the federation’s report to the JEP, leading Alfonso to conclude that the search for truth and justice is one of the factors behind the surge in the persecution of members of the Colombian teachers’ union.

Ongoing stigmatisation

Aside from the report submitted to the JEP, another factor highlighted in the threat issued against Fecode in December 2019 was the unions’ involvement in the social unrest that broke out in November of that year and has since reached boiling point on several occasions. The national strike is ongoing, as is the persecution. Alfonso highlights the “brutal social media campaigns” against Fecode, a union that factions of the ruling Democratic Centre party have dubbed ‘Farcode’, accusing it of having direct links with the former FARC insurgency.

One of the flash points in the growing stigmatisation of teachers for their participation in social mobilisations and the defence of critical education was the threats against Fecode’s leaders. Nelson Alarcón, former president of the union federation and a member of the national strike committee that was negotiating with the Duque administration, had to leave the country for around 40 days. The death threats continued on his return. In October, Colombia’s trade union centres reported that at least 32 acts of violence had been perpetrated against trade union leaders during the strike.

For CUT president Francisco Maltés, stigmatisation is “the prelude to murder. Wherever there is stigmatisation, violence is bound to follow; the result is not only the killing of trade union leaders but also their exile, and silence”.

Viviana Colorado, for her part, points out that, according to ENS monitoring, although fewer threats are documented today than in the past, “the violence is more focused on trade union leaders”. Whereas the cases of violence against visible leaders used to be around 30 per cent, this figure had risen to 90 per cent by 2020, says the researcher.

One of the departments where the intimidation has worsened as a result of the recent protests is Valle del Cauca, one of the epicentres of the national strike and one of the regions where the police crackdown was the most brutal. Anthoc leader Darwin Duque reports that, at the beginning of September, a member of the union’s executive board in the municipality of Yumbo was directly threatened and physically assaulted by a man and a woman. “This local branch leader played a very active role in the strike action,” says Duque, to explain the reasons behind the attack. He also highlights the fact that the threats are increasingly targeted at trade unionists in leadership positions.

The present-day situation of the Colombian trade union movement is far from encouraging. The nine murders, four attacks, 52 threats, 25 acts of intimidation and 11 arbitrary arrests committed during the first nine months of 2021 bear witness to this. In May 2021, Colombia was once again called on by the International Labour Organization to respond to allegations regarding freedom of association in light of the acts of anti-union violence reported since the signing of the peace agreement.

For Colorado, this call is “an alarm signal”, in a country where the trade unions are challenging the impunity surrounding the violence of the past whilst still struggling to survive the violence of the present.