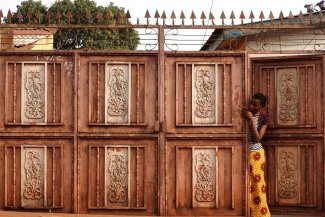

Guylaine, in this 7 February 2022 photo, works as a domestic employee in the city of Goma, in eastern DRC, to support her family and child. Her earnings amount to US$25 a month.

Victorine Muburwa has been working as a domestic worker – or dada as these women are commonly known in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) – for almost 13 years, since her husband died, leaving her alone with two children to support. Like many domestic workers, this woman, now in her thirties, never signed a formal employment contract with her employer. “In the course of my work, I have never come across or heard of a contract. It never crossed my mind, as an uneducated person, that a simple domestic job might also require a written document between the employee and employer,” she explains to Equal Times.

In July 2021, Victorine joined the Union des Femmes Domestiques du Congo (UFEDOC), a women’s association that campaigns for the rights of domestic workers.

Having not studied beyond primary school, she thought that employment contracts were only for office, company or NGO workers. “Thanks to UFEDOC, I found out that our work as domestics is like any other work and that a written contract is essential to protect us and to prevent either party from violating the agreements,” she adds.

A 2015 survey by the Belgian-African cooperation network IDAY found that poverty is the main reason for choosing this occupation, and that “17.6 per cent of Congolese domestic workers have no schooling. The figure is as high as 77 per cent in Orientale Province.”

The lack of awareness and understanding of their rights is among the factors exposing them to abuse at the hands of their employers.

It was in a bid to counter this that UFEDOC was founded, in 2018, under the leadership of Alexandrine Nabintu and Linda Buleso, both former domestic workers. The difficulties they themselves were experiencing at work made them increasingly aware of the need to set up an organisation to promote their rights and those of their colleagues. “Our aim is to help bring about a reduction in the exploitation and violation of domestic workers’ rights, to ensure sustainable development,” says UFEDOC coordinator Nsimire Nyenyezi.

Solidarity and group counselling

“We were able to set up a committee along with other women’s associations who agreed to join the cause. The short-term objective is to become a dynamic and formal trade union, to better defend the rights of domestic workers,” says Charles Mihigo, mobilisation officer at UFEDOC. The organisation has already affiliated with the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF).

Although the organisation’s name refers only to women, a number of men are also members of the association. It currently brings together more than 450 domestic workers, informing them of their rights and raising awareness among their employers, through home visits. It, above all, organises group counselling sessions, which help those attending understand that they are not alone.

“Some of them are confronted with similar difficulties: non-compliance with verbal agreements, withholding of wages, excessive hours, contempt…[.] We organise them in discussion groups in which they feel free to share their experiences, taking advantage of the opportunity to unburden themselves, to help heal their woes,” the coordinator adds.

“Having found that most workers suffer from trauma and abuse in the household, including sexual abuse, we also offer psychosocial support,” says Nyenyezi, adding that legal support is also scheduled to be introduced in 2022.

“Domestic workers find it very hard to report these abuses, as they work in isolation and it is their word against the offender’s, with few sympathetic witnesses willing to come forward. These workers also fear being fired if they report sexual harassment or rape,” says Bora Francine, in charge of handling the violation cases reported to UFEDOC.

Ratification of ILO Convention 189

Informal work is found in nearly 70 per cent of all economic activity in the DRC. For domestic workers, routine informality is not an exception. They are, however, a particularly vulnerable category of workers, as they often work in isolation, for private households. And because they are not declared, domestic workers are rarely paid at the guaranteed daily minimum inter-professional wage rate, which was set at 7,075 Congolese francs (US$3.50) in January 2018. They currently earn between US$20 and US$50 a month, which is unfortunately lower than in other employment sectors.

UFEDOC is advocating for the sector to be properly regulated in the DRC and is calling for the country to ratify ILO Convention 189 (adopted in 2011) on decent work for domestic workers. Only 35 countries have ratified it, to date.

“One of the major challenges we face is to secure the ratification of C189 and its implementation, which will in turn make it possible to adjust the legislation and continue to make progress for domestic workers until we secure the right to an eight-hour working day, a minimum wage and paid holidays,” explains Mihigo.

According to human rights defender and lawyer Billy Mbuyi, real gaps in the local legislation are at the root of the lack of protection for domestic workers in the DRC.

“The law needs to put domestic workers on the same footing as all other workers and treat them like any other employee. The specificities of domestic work are not taken into account.”

The IDAY survey also found that when a verbal or written contract is concluded between a domestic worker and his or her employer, the terms mainly refer to the tasks to be performed, the pay and the working hours. But there is no mention of its duration, rest periods, nor access to health care.

Furthermore, while the labour law provides for a weekly rest day for all categories of workers, in practice, this right is often disregarded and remains subject to the employer’s goodwill. Similarly, overtime is often unpaid.

Pascaline Ombeni, a mother of five in her thirties, experienced this while working as a domestic employee in Goma. She tells us her story: “My employer and I agreed that I would mop the house, do the laundry and the dishes, and then go home. But, a few days later, she started adding more tasks and extending my working hours without referring to our verbal agreement.”

Pascaline recalls that there were times when she had to work until 8pm, without her employer increasing her pay. “Although I am a mother and was barely making US$25 a month, she ended up telling me that I would have to work all day and spend the night at her place, as the tasks were piling up. But I couldn’t agree to that. Still, she fired me and withheld two months’ pay from me on the grounds that I had broken her precious cups and other kitchen utensils,” she explains.

The length of time most employers hire a domestic worker for is between one and two years, which is relatively short. Only a minority (2.7 per cent of domestic workers) remain with their employer for more than five years, making the level of horizontal mobility very high among domestic workers.