It looks clean and exuberantly beautiful, but the lake is contaminated. And the lives of 700 people depend on this lake, all residents of the Manos Unidas (United Hands) Cooperative, a community that is part of the municipality of Sayaxché, in the Petén department, northern Guatemala.

Manos Unidas has become the last frontier of resistance to the advance of palm oil production in the region, as the only community that has hung on to its land ; and that, say its residents, is because the lands are common property.

The collective ownership of the land complicates the strategies of the palm oil companies which forced the farmers in neighbouring communities to sell, using veiled threats and obscure arguments according to the three communities visited for this report. For this reason, and thanks to the tenacity and political awareness of these people, Manos Unidas still owns land for cultivating sweet corn and beans, and for renting out to families from neighbouring communities.

That does not mean they have escaped the impact of oil palm cultivation. The lake they get their water and fish from is polluted, and their harvests have been affected by the climate change resulting from deforestation : more heat and less rain. They also say they have felt the impact of the agro-chemicals applied to the palms, and increased infestations.

“Before, we didn’t use chemicals, but now, if we don’t apply fungicide, we can’t harvest anything,” says one of the community members. This witness, like everyone interviewed, asked to remain anonymous. In a country which, like Honduras, Colombia and Brazil, bears the sad distinction of being one of the most deadly in the world for the defenders of land and human rights, anonymity is a necessity.

The exuberant fertility of nature in Petén contrasts with the abandonment experienced by its residents. Running water, waste collection or sewage networks are all unthinkable in this corner of the world. But until palm cultivation arrived, about 15 years ago, water was not a problem ; today the hand dug wells are drying up and many communities have ended up being dependent on polluted water from the lake or the La Pasión river.

The ecocide of the La Pasión river

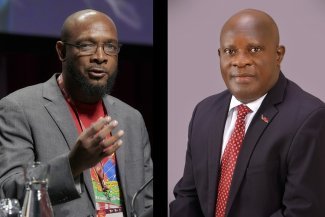

“Hugo Molina brought palm cultivation to Petén. Until about 15 or 20 years ago, this was pure forest,” says Rolando Pinelo from the Sagrada Tierra (Sacred Land) organisation. The initials of the name Hugo Alberto Molina Espinoza, considered one of the country’s biggest landowners, gave the HAME Group its name. It is the owner of Reforestadora de Palma del Petén, S.A. (REPSA, or Petén Palm Reforestation), as well of other brands such Olmeca.

The company became famous for the wrong reasons when, in 2015, it became known that it was directly responsible for the ecocide in the La Pasión river in Sayaxché. The case became stained with blood when a farmer, Rigoberto Lima, was murdered for denouncing the ecocide. His killer continues to walk free.

“The oxidation pools overflowed, causing an enormous death toll among the fish and polluting 150 kilometres of river,” explains Saúl Paau, the lawyer in charge of the case.

He points out irregularities that have enabled REPSA to continue its operations without monitoring. Even “the Ministry for the Environment recognised that there had been no Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA),” says Paau.

The authorities refused to analyse the river’s water, but the University of San Carlos carried out a study that detected the presence of an agro toxin used in palm production : Malathion. “Another report showed that the river would need five years to recover : but three months later they are fishing there again,” states Paau.

In the San Juan de Acul community, most people bathe in, cook with and even drink this water, even though they know it is polluted. They don’t need any studies : their vomiting, fevered and itching bodies tell them. But there is no other source of water and the state even refuses to let them have the tanks they have asked for to collect rain water – rain that is ever more scarce, again because of the climate change that is being accelerated by monoculture.

In addition to polluting the water, the ecological disaster in the river has put an end to the community’s principal source of food : fish. “Before, in two days we could catch 50 pounds of fish : today we are lucky if we can get ten or 15, and sometimes it’s not even that much,” a local fisherman tells Equal Times. He warns : “Without water we can’t live : without water there is nothing”.

Modern slaves

The only solution to hunger and thirst is the same thing that caused it : palm cultivation. Desperation has led these farmers to accept working conditions reminiscent of the days of slavery. A farmer from San Juan de Acul explains : “They work long hours for little money, with no fixed working hours, and they have to buy their equipment themselves. But there is nothing else. If there were another source of income, they wouldn’t do this, but we have to eat.”

“Most people here work on the palm plantations. They leave here at five to get to the plantation at six, and working until three in the afternoon, for a daily wage of 60 quetzales (about €7.50), which is less than the minimum wage (83 quetzales per day in rural areas, which is approximately €9.50).

“When pay day comes, they don’t want to pay them. They treat them badly and threaten to throw them out if they protest,” says one of the El Mangal community leaders.

One of the workers describes his working conditions : he works from six in the morning until three in the afternoon for 60 quetzales per day, but in some cases they are only paid 20 quetzales (less than €3) for the same working day.

“Sometimes they pay 45 cents (€0.05) for each root cut. But the hardest blow is that they only want young people. They bring in people from outside and they only keep them for a short time, to save money on social charges. They are ruining us, they are ruining everything. But need is driving us to the slaughterhouse. We have families to support. If one of our children falls ill, we can’t get medicine for under 70 quetzales (about €8.00).”

And after the palm tree plantations ?

“The remaining areas of forest are very small, they are not enough to purify the air. In the last downpour, the water was black. I had to throw half a bucket away,” says a local female farmer. And the rain is becoming increasingly scarce, while the land is dying.

“They are killing the land. The roots spread across the land and let nothing grow above them.” Which is why they are worried about what will happen when the palm plantations go. “After 25 years of palm cultivation, this land will be worth nothing.”

What is certain is that a study carried out in Valle de Polochic by the researcher Sara Mingorria of the ICTA (Autonomous University of Barcelona) shows that, due to the large quantity of nutrients it requires, oil palm monoculture removes the organic layer from the ground leading to infertility.

It takes 25 years for a zone where oil palms have been planted to become fertile again because “the soil is so weakened that, however much you fertilise it, the components are lost and disappear,” explains Mingorria. She adds that these plantations are usually called “green deserts” because “this type of tree does not allow any other vegetation to grow around it”.

When this happens, if they are not stopped by the stubborn resistance of indigenous and farming communities, the companies will look for a fresh piece of land to make profit from their investment, leaving behind them desertified land, polluted rivers and towns stripped of their livelihoods. All for the sake of profiting from a commodity whose stock is rising on the financial markets.