Après l’abattage, les carcasses de vaches sont exposées à l’entrée de l’abattoir. C’est d’ici qu’elles sont vendues aux détaillants qui en assurent la livraison aux consommateurs de la ville.

A mess of cow entrails and coagulated blood cover the floor of this colonial-era building. Visitors are immediately struck by the sound of clinking knives and bellowing cows. Located in the Ndendere district of Bukavu in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), this slaughterhouse produces most of the meat consumed by the city’s inhabitants. Before breathing their last breath, the cows struggle violently, covering the workers surrounding them in blood. Ultimately, their kicks are no match for the knife that has been driven into their heads.

Located on the banks of the Ruzizi River, the natural border between the DRC and Rwanda, the ‘Ruzizi 2’ public slaughterhouse is the largest in South Kivu province. Mugisho Biringanine, a 28-year-old butcher, grew up in the area and currently lives on the outskirts of Bukavu.

His clothing covered in blood and a knife in his hand, Biringanine waits his turn. He has yet to slaughter a single cow today. This is unusual for the young butcher, who has already worked at the slaughterhouse for 15 years. “I hope that by the end of the day I will have enough to feed my children,” says a worried Biringanine. His mother, a meat seller, introduced him to the trade when he was only 13 years old. Two years later, Biringanine dropped out of school and devoted himself entirely to his work as a butcher. He has no work contract and is paid by the job. “This job allows me to live. If I slaughter a cow and skin it, the boss gives me a piece of meat and US$10,” explains the father of five. This income has allowed him to feed his family and pay for his children’s schooling.

A union without resources

Biringanine is one of a hundred or so butchers who used to make a decent living doing this work. But ever since the Congolese government authorised the import of Rwanda-produced meat, times have been difficult.

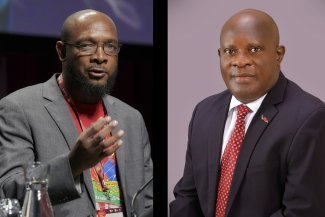

“The Rwandans used to provide us with cows. We would slaughter them and provide meat to households in the city. In recent years, we realised that the Rwandans were also starting to supply meat from their own country, which disrupted our business. As a result, over 80 per cent of the butchers here have stopped working,” says Dunia Mukubaganyi, vice-president of the Butchers’ Association of the Ruzizi 2 public slaughterhouse.

Membership in Mukubaganyi’s union has plummeted as a result. “Our association had more than 100 members. Today, there are only about 15 left. All the others have left the profession because unfair competition has destroyed their business,” he explains. As small traders, members of the union pay the annual patente, a tax paid by all traders who are unable to register with the trade register.

Founded more than 10 years ago, the organisation advocates on behalf of butchers. Despite numerous letters to the relevant authorities, their fight against competition from foreign butchers, who do not pay the slaughter tax and can thus offer lower prices, has produced no results. “The authorities have abandoned us. We pay taxes but we are not protected. All of our members are becoming poor,” says Mukubaganyi, whose union lacks the resources it needs to protect butchers. “In the beginning, we contributed US$0.5 to our fund every week. When a member got sick or had problems, our union helped them pay the bill or meet other expenses,” recalls Biringanine.

“Competition has destroyed our union. The authorities have been corrupted by foreign businessmen. It’s a problem for the state too because importers don’t pay the slaughter tax. With no oversight of slaughterhouse conditions abroad, there’s no way to protect consumers,” says Mukubaganyi. To avoid collective bankruptcy, the union is asking its members for a show of solidarity. “We are asking our members to reduce the number of cows they may have slaughtered in the past in order for everyone to earn some money.”

When the privately-owned Compagnie d’élevage et d’alimentation du Katanga (ELAKAT) established the slaughterhouse in 1958, it had modern equipment, a laboratory and cold rooms. The animals slaughtered then came from Katanga, in the southeast of the country. “All that is history now. Today we have no laboratory or instruments to carry out tests to ensure that cows are not sick,” explains Justin Cibalinda, veterinarian and deputy manager of the slaughterhouse, which was nationalised in 1971 along with many sectors of the economy following the DRC’s independence.

“We just observe the symptoms before and after slaughter. If we don’t notice any lesions during our observations, we conclude that the meat is fit for consumption. We don’t even have a microscope here,” says Cibalinda.

Such working conditions endanger consumers, potentially exposing them to illness and poisoning that can be fatal for people in poor health. According to a 2012 study entitled Assessing the Health Risks Associated with Cattle Slaughtered at the Public Slaughterhouse in Bukavu, conducted by researchers at the local university : “The quality of meat consumed in the city of Bukavu is precarious and exposes both the consumers and the cattle of the region to several health risks.” The study concludes that more than 22 per cent of the 800 animals studied were slaughtered during pregnancy, which not only produces meat that is unfit for consumption but also represents a violation of ethics and animal welfare. The cows studied were also exposed to parasites, such as flies and ticks, and carried microbes, among which strongyles and taeniasis were predominant. Ten years later, nothing has changed in this slaughterhouse.

Janvier Makombe, president of the Ligue des consommateurs des services au Congo-Kinshasa (LICOSKI), an association that defends the interests of consumers in the DRC, expresses similar concerns : “The cows are slaughtered on the ground. This exposes the meat to the risk of infection. We have witnessed cases where cows have been slaughtered while carrying diseases. Due to the lack of cold storage, the meat is poorly preserved and causes many outbreaks of food poisoning,” explains Makombe.

According to Makombe, several people who have consumed the meat sold on the local market have gone on to develop symptoms. “We saw one person develop severe skin lesions after eating poorly preserved meat. We see unfit meat being sold on the market every day. Some of the meat has already changed colour by the time it arrives on the market,” he says.

In addition to consumers, the butchers at the slaughterhouse are also constantly exposed to risk. Without the necessary protective equipment, cows’ horns and kicks can cause accidents and lead to disabilities. Touching the cows without protection also exposes butchers to several types of disease and infection.

Insufficient state services

But despite these dangerous conditions, business is booming. Every day, about 25 cows are slaughtered at Ruzizi 2. “Meat is considered a staple food. Meat consumption in the city is increasing every day,” says Cibalinda. Without sufficient data, it is impossible to determine the amount of meat consumed daily. However, one thing is certain : large numbers of cows are regularly sold in Bukavu. Every day, more than 100 cows cross the Congolese border. While some of them are slaughtered in Bukavu, others are transported to towns as far as 100 kilometres away.

The meat consumed in Bukavu used to come from Katanga and the villages of South Kivu ; it now comes from other African countries. “Intermediaries buy cows in countries like Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda and sometimes Senegal, and bring them here to sell,” says Cibalinda.

According to the former farmer, the violence gripping many villages in the DRC has impoverished local herders, who are no longer able to supply the city with cows as they once did.

Under-resourced state services are unable to monitor the quality of the meat consumed in the city. The Office Congolais de Contrôle, the institution responsible for inspecting the quality of products sold on the market, has no local office. To make ends meet, government employees are forced to rely on the charity of butchers. “The majority of civil servants receive no salary. If a butcher is generous, he gives us some money or a piece of meat after the inspection. That’s how we get by. We don’t even have vet’s scrubs,” laments Cibalinda, a government employee.

However, he remains hopeful. “I hope that one day we will have a laboratory and cold rooms to better serve consumers. I hope that I will be listened to and given the necessary means to properly carry out my work,” he concludes.