Waste on a beach in Cornwall, United Kingdom, in September 2017.

Bottles, cotton buds, straws, corks: a whole host of plastic waste items were collected by Simon and about 20 other volunteers on Hell’s Mouth beach in Wales, in the United Kingdom, on 15 September. It was World Cleanup Day, a major international waste clean-up operation launched by the civic movement Let’s Do It! World.

Millions of people across the globe were invited to arm themselves with gloves and waste bags and to collect the litter lying around in city centres, in the countryside and on the coast. Simon, who pioneered an initiative to encourage people to pick up at least five pieces of litter a day, and who organised the clean-up at Hell’s Mouth, explains: “I live close to the beach and spend a lot of time in nature…and I see the damage we are causing with the masses of plastic that get washed up each day on the shores.”

Ian, who also took part in the clean-up, expressed his “surprise” and “sadness” at the amount and the range of items collected. “We’ve got to do something now, we can’t leave it on our children’s shoulders or on our grandchildren’s shoulders.”

Let’s Do It! World, for its part, explained: “Our aim is to help create a ‘zero waste’ society, where things like single-use plastics are a thing of the past, where effective waste management systems prevent pollution and where industries and governments not only combine to help us recycle what is wasted but also to prevent waste in the first place.”

A danger to marine environments

Lightweight, resistant and inexpensive, plastic is widely used in our societies. The problem is that it generates a huge amount of waste. In 2016, 335 million tonnes of plastic were produced worldwide to satisfy our appetite for disposable cups, bags, toys and other items. This gives us some insight into the impact on our oceans today, with part of this plastic unfortunately ending up at the bottom of the sea. An estimated 8 million tonnes of plastic waste enter the marine environment each year. And at least 150 million tonnes are thought to be already out in the open sea.

The consequences are clearly catastrophic for marine life. “Plastic can be ingested by animals,” we are reminded at the Marine Conservation Society, an NGO fighting to protect marine environments in the United Kingdom. “The northern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis), for example, that we find on Atlantic coasts, is a bird that feeds on plankton floating on the sea surface, and the species is found to very regularly eat bits of plastic. There are also many animals that are known to get entangled or trapped in plastic items, particularly fishing rope and nets but also plastic bags and bottles.”

According to a United Nations report published in 2016, nearly 800 animal species were already known to be affected by marine debris, most of which is plastic.

A study published in June found widespread microplastics in mussels from UK waters. The health implications for humans have not yet been studied.

Reduce plastic at source

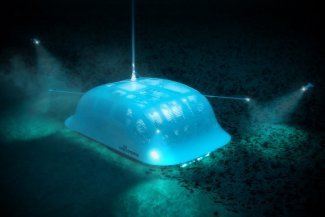

Clean-up operations are an essential way of trying to improve matters, of course (such as the innovative device invented by Dutchman Boyan Slat that is currently tackling one of the large patches of waste floating in the Pacific), but they do not solve the problem. Plastic production must be reduced at source and ways must be found to prevent waste from entering the environment.

Consumers are being called on to be more careful, to shop with reusable bags, to refuse plastic straws and cutlery, or to refill water bottles rather than buying new ones. This is the aim of the Refill Campaign seeking to reduce the use of plastic bottles by encouraging the British to go to the nearest water fountain or “refill stations” offered by local businesses.

But companies and governments also need to do their bit, otherwise individual efforts will not amount to much. More and more regions around the world are taking action against single-use plastics. One of the main targets is plastic bags, which are used for 20 minutes on average and take around 400 years to decompose.

Bangladesh was the first to ban them, in 2002. They had been pinpointed as causing severe flooding by blocking drainage systems. In Rwanda, fines and prison sentences have been put in place for those refusing to comply with the ban.

In 2015, the European Union took measures to reduce plastic bag use. This year, the Commission proposed a ban on single-use plastics such as cotton buds and plastic straws or cutlery. Aside from the fact that they account for huge quantities of plastic, are only used for a very short space of time and are often found littering natural environments, another argument for putting an end to single-use plastic items is that it wouldn’t create any major problems, unlike some types of packaging needed to preserve food, as the environmental association WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature) explains to us.

Better waste management

In addition to plastic reduction measures, emphasis must also be placed on its reuse. And we still have a long way to go. Since the 1950s, 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic have been produced worldwide, generating 6.3 billion tonnes of waste. Only nine per cent of this has been recycled. In Europe, where the recycling rate is the highest in the world, only about 30 per cent of the plastics collected are recycled, which isn’t much.

In its strategy, proposed in January, the European Commission recommends increasing the circularity of plastic, by encouraging producers to redesign their plastic packaging to make it more recyclable, for example, or by creating quality standards to encourage the recycled plastic market, which remains underdeveloped. The EC’s idea is to achieve the target of 100 per cent recyclable or reusable plastic packaging by 2030.

Since pollution knows no borders, the fight must also be global. Unfortunately, some states are more implicated than others. China, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam were identified, in 2015, as the main sources of plastic waste leaked into the ocean. With their large populations and booming economies, these countries are producing an amount of waste that they are currently unable to manage properly.

This is all the more worrying given the amount of waste they import from other countries. At the beginning of the year, China closed the door to several types of waste, creating a wave of panic amongst the countries exporting it, especially in Europe. Ocean Conservancy, a US environmental protection NGO, author of a report on the solutions to be brought in that part of the world, is nonetheless optimistic, underlining the “huge increase in awareness of and engagement in this issue across the region”. The NGO has estimated that better waste management in those countries and in Thailand, could reduce global plastic leakage into oceans by 45 per cent in ten years.