In this August 2021 photo, student members of the Slam at School programme perform their poems at the Don Bosco Institute in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo.

On a July morning at the Sainte-Ursule Lycée in Goma, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, students taking part in an open-air slam poetry performance recite texts calling for gender equality, social justice, child protection and human dignity. They have been introduced to this poetic and oratory art by the Goma Slam Session collective.

“In Africa, we are taught not to criticise the boss, we don’t say ‘no’ to our father, we don’t assert our rights, we are told that women belong in the kitchen and school is for men. As artists, we use slam to assert our rights, to break taboos and prejudices,” explains Ben Kamuntu, a member of the group that has as many as 90 participants.

It was in 2017 that Kamuntu and his friends founded this collective to provide a forum for expression and exchange through slam poetry, sometimes recited against a musical background. The country was in the midst of a transitional period, with former Congolese president Joseph Kabila clinging to power, although his term had come to an end.

“We made a wish for our country for the coming year: a wish for justice, for a democratic Congo where a president can leave power and make way for someone else in accordance with the constitution. Then we did a piece of slam poetry together, with each of us making a wish,” recalls the young man.

It is in a lively neighbourhood of Goma that the group offers a meeting place designed to promote free thinking. Rehearsals and slam sessions are held there every Saturday, providing an opportunity for the participants to share texts, to critique and to correct each other’s work.

“There were poets in Goma, but they were poets without a platform to bring them together and provide them with a framework for expressing themselves. Our slam sessions give everyone a chance to speak. There is no boss and no uniformity here. We advocate plurality, strength in numbers,” says Depaul Bakulu, a member of the collective. “The more there are of us defending the same cause, the more our voice is heard.”

Activism in Bujumbura and Antananarivo

In Africa, poetry competitions around the fire were once part of the oral tradition. They bear a striking resemblance to those emerging in the West in recent years. Modern slam is considered the poetic form of the 21st century. It emerged in the United States in the 1980s and started to develop in France in the 1990s. Between oratory contests and improvisation, the art of storytelling has been kept alive and enhanced by the blend of tradition and modernity.

In DR Congo, Madagascar or Burundi, it plays a crucial role in people’s daily lives and appeals to almost everyone on public stages throughout the continent.

It was around the year 2000 that modern slam started to flourish in the Congolese capital, Kinshasa. Many slammers have emerged whose texts are often politically engaged, dealing with political issues and the humanitarian crisis in the east of the country, as well as more personal and poetic texts.

In Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi, be it parents and children, or even pupils and teachers, it is an art form that resonates with all those who listen to it. “As artists, we do our best to recount the daily life of Burundians through a variety of themes,” says Junior Adasopo, a member of the Burundian slam poetry collective, Jewe Slam.

“Slam poetry is more than an art form for me, it is a channel for free expression and a way of life,” insists Kerry Gladys Ntirampeba, another member of the group.

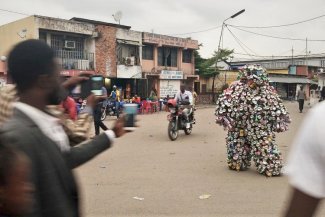

In eastern DR Congo, the Goma Slam Session collective holds a public event every last Friday of the month. During one of them, participants called for dignity for prisoners and the recognition of the victims of the massacres in Beni, North Kivu. Most of the performers are young activists who dream of a fair world with fewer social inequalities.

For 21-year-old Feza Eliane, slamming is the ultimate way of speaking out against and dealing with injustices. And it has changed her life: “I have no other meaningful way of defending human rights. More than being a passion for me, it has become my everyday life. And since my life is a struggle, slamming is my ultimate driving force,” she tells Equal Times.

In Antananarivo, in the heart of Madagascar, slam poetry artist Caylah has already made a name for herself with her slamming style. Crowned slam poetry’s national ‘Champion of Champions’, in 2014, she has invented what she calls ‘slam therapy’, to cure ills through the spoken word. Famous for her Madagascar piece, released in 2016, she expresses her feelings about her island, a country plagued by political and economic instability since colonial times.

“Madagascar is my first text in Malagasy. I’d written mainly in French till then. And it took me a long time. It is a plea from the heart, a message to politicians. In short, it’s the opinion of an ordinary Malagasy citizen,” she explains. Through her work, the 26-year-old seeks to encourage women, and especially young girls, to express themselves and stand up for their rights. “Slam has saved me and I would like to do the same for others. I have no money. My talent is my only way of restoring hope,” says Caylah.

Malala adala (“madly in love” in Malagasy) is an ode to all women who have to fight and to those suffering from domestic violence and the preconceived ideas plaguing Malagasy society. “When I was younger, I was a victim of school violence, which also pushed me to write down what I felt in my diary,” she confides. “I was six years old and I was looking for peace and tranquillity. And because I love philosophy, I found it had a certain poetry to it,” says Razanadranto (Caylah’s real name) to explain how she came to embrace slam poetry.

Taking slam into schools

Since 2019, the Goma Slam Session has been introducing youngsters to the art of oratory, teaching them the rules of poetry, and raising awareness about gender, human rights, the environment, child protection and responsible citizenship. Its Slam at School programme is designed for girls and boys aged between 10 and 17. More than 18,000 youngsters from 18 schools in Goma are benefiting from it. The latest workshops were organised with support from the Italian NGO Volontariato Internazionale per lo Sviluppo (VIS - International Volunteering for Development).

“We consider it crucial to bring free speech back into schools, to provide this opportunity for self-expression, because it’s a necessity. It’s giving them something that the school system doesn’t offer,” says Kamuntu.

Franck, a young student from the Zanner Institute in Goma, also took part in the workshops: “The programme has helped me to develop my critical thinking skills, my freedom of thought and even my self-esteem.”

Robin Businde, another young beneficiary of Slam at School, agrees: “Now I am able to organise my texts well and I can write on all kinds of topics. I’m able to stand freely in front of people without fear. And what’s even more interesting is that I’m able to develop a flow of my own.”

Ben Kamuntu is also a member of the Lucha (Fight for Change) movement. In March 2021, he released Bosembo (’Justice’, in Lingala), a hard-hitting piece of slam poetry calling for justice for crimes that have gone unpunished in the DRC for over 25 years. He is campaigning for the creation of an international criminal court for the DRC and has added his voice to that of Congolese doctor Denis Mukwege, winner of the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize.

The lyrics of Bosembo are inspired by the 2010 UN Human Rights Mapping Report, which documents years of war crimes and crimes against humanity, as well as potential acts of genocide in DR Congo.

“Bosembo is a slam that is linked to my own life, to my journey, that of a young person of the 1990s generation. It is the fruit of my frustration, my revolt, of all the years of war that we have lived through and continue to live through here in Kivu,” he confides. “Millions of Congolese have been killed since the 1990s. Bosembo is about all the crimes that have been committed here. It is a contribution to the appeal for transitional justice as a guarantee of peace in the Congo. Because impunity fuels the cycles of violence.”