Ten years ago, the International Labour Organization (ILO) adopted Convention 189 and Recommendation 201 on the rights of domestic workers. Since that ground-breaking step, 35 countries around the world have ratified C189, but only seven of them are in the Commonwealth, which covers a third of the world’s population and has over 50 member states. Over the past 18 months, the Covid-19 pandemic has demonstrated just how vital care work is, and yet domestic workers – mostly women – have been among the hardest hit by the effects of the pandemic. It has shaken the job and income security of millions of domestic workers, putting them at greater risk of abuse, exploitation, and trafficking.

On International Human Rights Day, (10 December) a new report from the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), supported by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and the Commonwealth Trade Union Group, has explored the experience of domestic workers in the five Commonwealth countries which have ratified the Convention, four countries which are considering ratification, and some of those who haven’t even gone that far.

Case studies and analysis show that the call for the wide ratification of C189 by human rights NGOs like CHRI, trade unions representing domestic workers, and domestic workers’ groups (many of which are part of the trade union movement) are fundamental in the fight to end the abuse and exploitation of domestic workers. This call to action forms an intrinsic part of the global care economy agenda which requires increased investments in care, including the creation of millions of decent care jobs, and the transitioning of informal care jobs to formal jobs with decent pay and working conditions as part of a gender-responsive just transition to a carbon-neutral economy.

Since the Convention and Recommendation were adopted in 2011, the ILO estimates that there has been:

• a 15 per cent increase in the number of domestic workers who are included under the scope of labour laws and regulations;

• a 21 per cent increase in the number of domestic workers who are entitled to weekly rest of at least the same length as that of other workers; and

• a 12.6 per cent increase in the number of domestic workers who are entitled to a period of annual leave that is at least the same as for other workers.

And yet, many Commonwealth countries have not yet taken the necessary step of ratifying, let alone implementing the Convention, something the Commonwealth Trade Union Group called for in its submission to the September 2020 meeting of Commonwealth women’s and equality ministers, to address low wages, insecurity, and inadequate personal protective equipment in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic.

While Antigua and Barbuda and Malta are in the process of ratifying C189, and Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Mauritius, Namibia, Sierra Leone and South Africa have already done so, more than 40 Commonwealth countries have failed so far to ratify including Dominica, India, Papua New Guinea, Uganda (although the Hotels, Food, Tourism, Supermarkets & Allied Workers Union is hopeful of progress soon) and the United Kingdom, each the subject of a case study in the CHRI report.

In 2019 there were at least 75.6 million domestic workers aged 15 years and over globally, three-quarters of them female. Domestic workers usually work long hours for very low wages and are often excluded from labour and social protections.

Where protections and enumerated rights do exist in national legislation, there is a high risk of non-compliance due to the lack of adequate enforcement mechanisms including their right to organise and to collective bargaining. The risk of abuse and exploitation is even higher for migrant domestic workers, who have limited or no freedom to change employers, are often dependent on illicit recruitment agencies imposing exorbitant recruitment fees and stringent visa terms. The ILO estimates that, globally:

• 28 per cent of countries impose no limits on normal weekly hours of work for domestic workers.

• 94 per cent of domestic workers are not covered by all social security branches in their country

• 43 per cent of domestic workers are either excluded from minimum wage coverage or have a statutory minimum wage lower than other workers

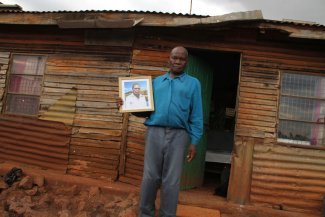

South Africa was the first Commonwealth country to ratify C189, largely because of the long tradition of trade unionism among the country’s 1.3 million domestic workers. Eunice Dhladhla, assistant general secretary of the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU) is quoted in the report, saying: “If you want to fight for your rights you must be strong and continue organising and recruiting. But you also must love the workers you are fighting for. Don’t help because you want to, work because you love them.”

As the nephew of two UK-based domestic workers, I want domestic workers around the world to have the same strong workers’ rights and recognition that I want all workers to have. This report is the start of a campaign to ramp up ratification of Convention 189 across the Commonwealth.