Photos by Isabelle Merminod

Four years after the revolution, Tunisia has a new constitution and recently had new elections. Despite all the progress made, there is still much more to be done and women remain on the front line in the struggle to build a new Tunisia.

On the occasion of International Women’s Day, we speak to six women determined to create a just society without violence.

Lina Ben Mhenni, blogger

Lina Ben Mhenni is a popular blogger who, on 30 August 2013, was attacked outside a police station by police…while under police protection.

“I created the blog A Tunisian Girl in 2007 [under the rule of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali]. I used to write for myself but I discovered the concept of blogging and I decided to share my writings with an audience. Human rights and liberty of expression became important. For me, the idea of censoring a blog is a sort of violence…you stop me from expressing myself. When they attack a female blogger, she is attacked because of her gender.

“Since the departure of Ben Ali [in 2011], the degree of verbal violence has increased. Because I am known, because I continue to criticise whether it is political parties in power or religious extremists, I have become the target of various attacks. I have begun to receive threats, serious [death] threats, which have forced the Ministry of the Interior to give me police protection. But even while under police protection, I was attacked by the police. Looking back, I see now that it was a planned attack and not a random event. Me, I’m not going to drop the affair. [The police] who were involved in the attack must be judged and punished. Unfortunately, today the security forces feel able to do what they want in the name of the war against terrorism. The justice system is dealing with it now. I will carry on, right to the end.”

Tunisia’s 2014 constitution upholds equality between men and women and also requires a gender balance in parliament – one of the few countries in North Africa and the Middle East to have such an obligation.

Mariam Touré, student and activist

Mariam Touré is a Malian law student in Tunisia. She came to the public’s attention after writing an open letter about racism published in October 2014, stimulating a much-needed public debate on the issue.

“Take my words as the cry of a lost sister who doesn’t understand why the colour of her skin would be the object of derision and mockery,” wrote Mariam Touré in her now famous open letter.

Speaking to Equal Times in 2015, she further explains: “Denial exists. They say, ‘what are you saying? Racism doesn’t exist in our country!’ But [it exists] in actions, in words, in the way of thinking. One day in front of a school with a friend there was a group of kids who started throwing stones at me, and insulting me. A child of seven! And in front was his father who laughed.”

But she adds: “Tunisia has hugely influenced me, above all the position of women in Tunisia. Tunisian women have a certain status. Tunisian women – even in relation to the law – are enormously protected.”

There are various NGOs working to combat racism in Tunisia such as M’nemty and the Association des Etudiants et Stagiaires Africains en Tunisie (AESAT) which works to protect the rights of sub-Saharan African students in Tunisia.

Basma Khalfaoui, lawyer

Basma Khalfaoui, pictured here with one of her daughters during a commemoration for her husband Chokri Belaid, the left-wing lawyer and vocal critic of political Islam. He was assassinated outside their house on 6 Feb 2013. Nobody has been charged with his murder.

“Just after the assassination, right after it, I said that one must never respond to violence with violence. I appealed to everyone to respond to violence with ideas and with words. Six months after this was my response to violence – the Chokri Belaid Foundation Against Violence. We have not got to the point where we know the truth and the whole truth about terrorism, not only about the assassination of Chokri Belaid. The assassination of Chokri Belaid is the gate through which you have to pass to get at the truth of terrorism in Tunisia. Who installed terrorism in Tunisia? Who has brought arms into Tunisia? How was it done?”

Last month, the press reported that Mohamed Salah Ben Aissat, the new Minister of Justice, had prioritised a new anti-terrorism law.

Mbarka Brahmi, politician

Mbarka Brahmi, pictured with her daughter Sara during a commemoration for her husband, Mohamed Brahmi. Mohamed was a left-wing deputy in the Tunisian parliament. He was assassinated on 25 July 2013 in front of their family home, less than six months after the assassination of Chokri Belaid. Nobody has been charged with his murder.

“At first we [Mbarka Brahmi and Basma Khalfaoui] were in the same situation, suffering the same pain, the same unhappiness, each of us reacted in our own way. Perhaps for me it was because Mohamed was a deputy.”

Mbarka decided to stand as a candidate in her husband’s seat in Sidi Bouzid, the epicentre of the 2011 Tunisian revolution. She is now a member of the opposition party Popular Front and was elected in October 2014. As a legislator, she sits alongside deputies from a party that is widely believed to have had a hand in the assassination of her husband.

She said to one of these deputies: “‘I have a political issue with you and there is a file against you going through the courts – but I cannot harm anyone. There are some members of that party who have never dared approach me…”

In 2014 Tunisians voted 68 women into Tunisia’s 217 strong parliament. Women now compose 31 per cent of the country’s deputies, a figure higher than France (26 per cent) and the United States (18 per cent).

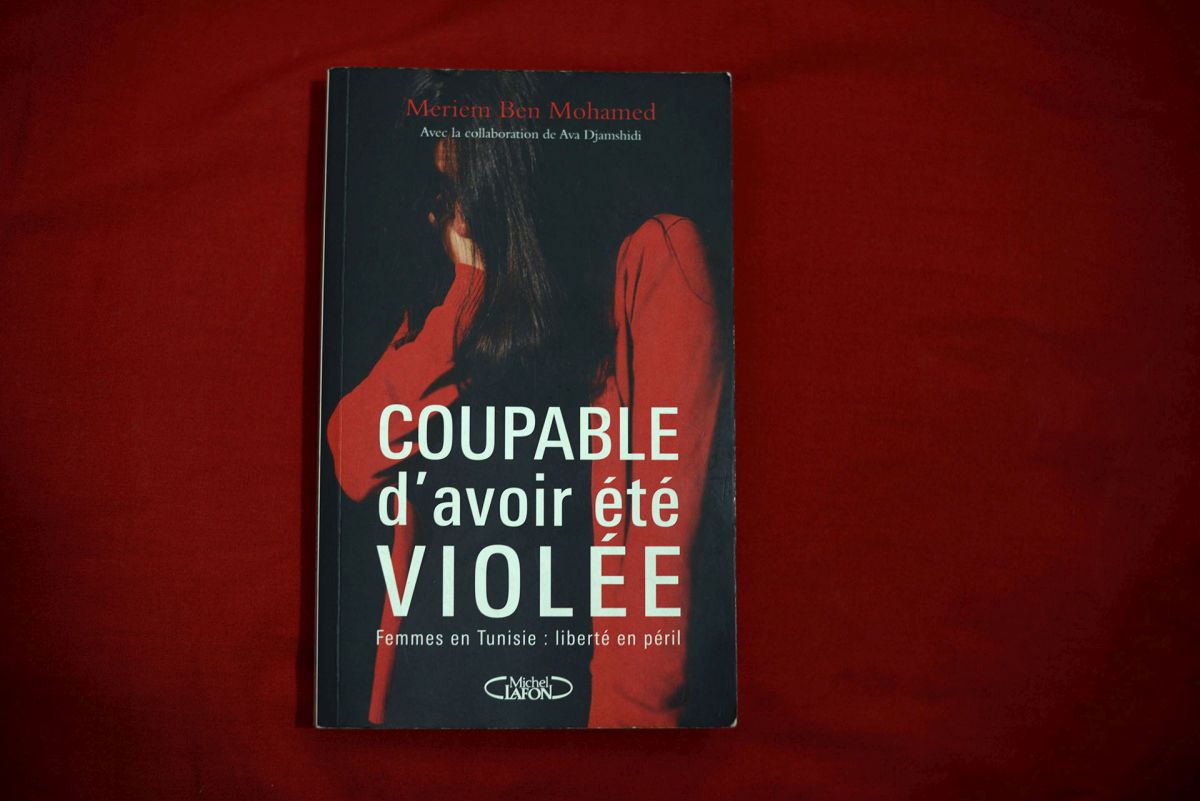

Meriem Ben Mohamed, rape survivor

Meriem Ben Mohamed was raped by two policemen in 2012 when she was 27-years-old. In order to silence her, she was accused of ‘offending public decency’ a crime which carries a six-month sentence. After international uproar, the charges were dropped and her attackers eventually received 14-year sentences. Meriem is the first woman in Tunisia to complete the process of pressing charges against police officers in a rape case.

“I would like them to get a very long sentence so that no policemen, or man, ever dares rape a woman again,” she explained to Equal Times before the final verdict was announced in 2014.

Meriem attended some 14 hearings over the course of 20 months, expecting each time to be her traumatic experience to a close. But each time, she confronted the judgment of a society in which a woman who has suffered sexual abuse is considered to have brought shame upon the family.

“The press took it up; in America also, and they sent a letter for the trial…That helped me because here in Tunisia, they are worried about the image of Tunisia internationally.”

Meriem is once again under investigation as her attackers have accused her of making death threats against them. “I have to continue. Perhaps when you have nothing more to lose you become stronger. It is a question of justice and I must continue.”

On April 23 2014, Tunisia lifted most of its opt outs the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

A draft law on violence against women was due to be presented to the Tunisian parliament in November 2014 but has been delayed.

Leila Gaaloul, textile worker

Leila Gaaloul worked for 26 years in the garment industry, most recently at the Belgian company Jacques Bruynooghe Global (JBG). One day in 2012, its 300-odd women workers arrived at 7am and found the gate was shut. The factory never reopened and no warning had been given. Leila now campaigns for the rights of textile workers with an NGO, the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights.

“Before the revolution it was better; [now] employers have taken advantage of the weakness of the state and the lack of inspections for more violations against our rights. I am unemployed now. I am ill and it is absolutely vital that I have healthcare and medicine. In two months I will not have access to medical care as my state health card runs out.”

Campaigners point out that many older factory workers suffer muscular and skeletal problems (RSI) as a result of having to repeat the same hand movements at work.

In June 2014, a Tunisian court passed a judgement in favour of 311 female workers who had been unlawfully sacked by JBG. The court awarded the workers approximately four million Tunisian dinars (approximately US$2 million) in back-pay, bonus payments and unlawful dismissal.

But the Belgium-based company is yet to make a single payment as it is out of the reach of Tunisia’s courts, although Avocats Sans Frontieres are considering whether they can pursue the case in Belgium.