Depuis le décès à l’âge de 9 ans de sa fille Ella, première victime officiellement reconnue de la pollution de l’air, Rosamund Kissi Debrah s’est muée en une infatigable défenseuse du droit à l’air pur. Londres, mars 2022.

Although Jo Barnes has been working on air quality for almost 20 years, it was only in the mid-2010s that this professor at the University of the West of England in the UK saw the emergence of a public debate on the social inequalities created by pollution. In other words, is clean air, that universal good par excellence, as equally distributed as it seems ? In 2003, a pioneering study in the UK suggested that it was not. Barnes and her colleagues went on to confirm “the presence of social inequality and environmental injustice” – the poor are often more exposed to pollution than the wealthy, and more vulnerable to its effects, even though they generate less. Linked to urban planning, housing and transport policies, it is a complex phenomenon that can be found in many European countries.

In the United States, these inequalities have contributed to the emergence of an environmental justice movement that has been active for some 30 years. In Europe, where air pollution with the finest particles is estimated by the European Environment Agency to cause up to 400,000 premature deaths per year and countless respiratory, cardiac and other illnesses, the debate is only just beginning. The European Commission’s Zero Pollution Plan points out that people “living in more precarious socio-economic conditions” suffer more than others, but the observation is slow to be translated into action. In France for example, anti-pollution measures are “too often applied uniformly across the country, whereas differences in vulnerability should be taken into account,” points out Séverine Deguen, a researcher who took part in Equit’Area, the first French research project on pollution and social injustice.

The struggle of a handful of parents from the Anatole-France school complex in the city of Saint-Denis, in the Paris region, is one of the rare examples of mobilisation on this issue in France. The levels of the main pollutants where this school stands, in one of the poorest communes in the country, already range between “bad” and “very worrying”, according to the measurements taken by associations. And with the works for the Paris Olympics in 2024, the school is going to be trapped between two huge motorways. “It makes no sense,” says Hamid Ouidir, a father of two schoolchildren. “We’ll end up with 10,000 to 20,000 cars a day on each side.” His struggle to press the authorities to overturn the decision is cited as an example in a 2021 UNICEF report on the overexposure of poor children to pollution. But Ouidir is one of the few people to take it public. “The campaign is not really taking off,” he admits, attributing the low level of mobilisation to the resignation of the local residents and to conflicts of interest between health issues and economic development.

From the UK to Romania, mothers lead the fight

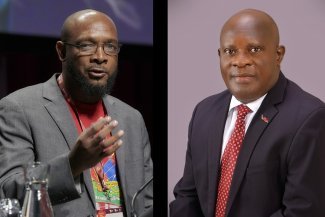

Some countries are making more headway. In the UK, there is renewed interest in air pollution and its inequalities, much of it thanks to Rosamund Kissi-Debrah. This Londoner fought to have the death of her daughter Ella, who died in 2013 from an asthma attack at the age of nine, attributed to pollution. The family was living in Lewisham, a borough that is in the 20 per cent of the most deprived local authorities in England. The family’s home is adjacent to the very busy South Circular Road. At the end of 2020, Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah became the first person whose death was officially linked to air pollution by a coroner. She is the only fatal victim with a name and a face.

Rosamund Kissi-Debrah has since become a tireless campaigner for the right to clean air. She has been lobbying organisations and politicians moved by her story to have the World Health Organization (WHO) pollution limits enshrined in law. She also reaches out to fellow citizens. When we meet her in a Lewisham café, she uses the opportunity to call out to customers with their babies in arms : “Do you know that the pollution in our neighbourhood is threatening the health of our children ?”

“Mothers,” she tells Equal Times, “like all those who care for children, are powerful mobilisers. I wish they realised the power they have.”

Kissi-Debrah shares this conviction with Mums for Lungs. This British association is fighting for ‘school streets’, pedestrianised zones near schools. Children themselves are more vulnerable to pollution and are potential activists.

In 2021, a group of teenagers, including one of Ella’s classmates, launched Choked Up, a campaign to alert the public to the health and social dangers of dirty air.

“Breathing kills. People of colour are more likely to live in an area with illegal pollution levels,” read signs posted around London. Around 100 doctors have backed them by writing to London mayoral candidates. Choked Up also teamed up with the Labour Party to release a study that found a correlation between the most polluted areas of London and those with the highest levels of child poverty.

We find ourselves 2,000 kilometres from London, in Cluj Napoca, one of Romania’s main cities. “This is our youngest activist,” says Stoica Maria Rozalia, nursing her five-week-old baby. Since she was five years old and her family was evicted from the city centre, Maria has lived in Pata Rat, a Roma neighbourhood of around 1,500 people set up on a landfill site. In a 2020 report, the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) called Pata Rat “Europe’s largest waste-related ghetto” and denounced the “environmental racism”. As a community facilitator, Maria Rozalia deals with administrative documents, organises activities for children and fights for access to drinking water and clean air. The fumes from the waste, and the proximity of the airport and major roads contribute to the high levels of pollution in the area. Most mothers see their children developing health problems when they start playing outside, at around age two or three.

Valuable support from scientists

“The illnesses I see most often are asthma and infections, such as tonsillitis,” says Bogdan Mincu, a Romanian pulmonologist. The doctor is doing his best to document the problem. In 2021, in association with the Desire Foundation, which is committed to combating social injustice and housing problems, Mincu conducted a study on health in Pata Rat – 83 per cent of the respondents said their children had needed medical care in the 12 previous months ; 50 per cent admitted to having a daily cough ; and most said they were “aware of the pollution”. The study found levels of fine particles exceeding the recommended thresholds. The same is true for hydrogen sulphide, a toxic gas that causes a bad odour, nausea and dry eyes and throat.

Scientists are playing a crucial role in supporting citizens’ struggles. By cross-referencing Ella’s asthma attacks with pollution data, immunologist Stephen Holgate convinced the authorities of a causal link in the UK. In Rybnik, a Polish city considered to be one of the most polluted in the EU, several studies have shaken up public opinion. This Upper Silesian city is known for its coal mines, but the pollution is also caused by domestic heating. In 2019, Monika Glosowitz’s three-year-old son participated in a study by the Belgian researcher Tim Nawrot.

The results showed that the urine of children in Rybnik contained three to nine times more black carbon, a toxic substance, than their counterparts in Strasbourg, France.

The team of Katarzyna Musioł, an oncologist and the medical director of the Rybnik hospital, also revealed that children in the city are more prone to brain tumours than those in other parts of Poland. The doctor has also observed a deterioration in their mental health – depression, concentration and behavioural problems – which she links to smog.

This research has helped build collective consciousness, according to Glosowitz. In 2021, after six years of struggle, a citizen of Rybnik won what he considers to be a ground-breaking victory. Oliwer Palarz, co-founder of Rybnik Smog Alert, was awarded €6,500 after a court ruled that his rights to health and freedom had been violated by pollution. Palarz hopes that other citizens will follow. But most residents are forced to take individual measures. Glosowitz has installed air purifiers and stays at home with her windows closed when the app measuring pollution shows high levels. She is able to stay indoors and work from home when the air quality outside is too bad, but not everyone can.

In recent years, some Polish provinces have taken steps to ban ageing coal-fired boilers. In Rybnik, the local government has created a number of public subsidies, some of which are available on an income-adjusted basis, to help households change their equipment. Since the beginning of 2022, those who do not comply will be fined. Time will tell whether the measure is sufficient to reduce the levels of pollution, the thresholds of which have hitherto been exceeded on 120 to 130 days a year.

Giving a voice to those most affected

In Romania, local authorities, including the Cluj Napoca City Hall, which did not respond to our interview requests, have created a programme that has already helped resettle some Roma in the city. Maria Rozalia hopes to benefit from it. But the Desire Foundation remains sceptical about the promise to relocate Pata Rat residents by 2030. Activists suspect that the politicians’ motives have more to do with the construction of a state-of-the-art complex, Transylvania Smart City, near the dump. “The authorities are more driven by financial incentives than human suffering,” sighs Mincu. The pulmonologist would like to convince them that fighting pollution also has economic benefits. “A child suffering from respiratory diseases has a high chance of suffering from COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] or pulmonary fibrosis in 40 years,” he warns. “Preventing them now means avoiding huge costs in the future.”

From her office in Bristol, British researcher Jo Barnes insists that air quality and social justice policies should not be top down but thought out and implemented with the communities concerned. Firstly, because certain environmental measures can penalise the most vulnerable by for example requiring them to give up short-term polluting equipment such as cars and boilers, without an alternative being offered. But also because some decisions increase the pollution suffered by poor households, for example by shifting traffic from city centres to the outskirts, where less privileged residents often live.

In Bristol, Residents Against Dirty Energy (RADE) wants to make their voices heard. The initiative was launched in Easton, a working-class neighbourhood affected by creeping gentrification and an environmental culture clash, according to Stuart Phelps, one of its organisers.

On the one hand, there are families who depend on cars for work – many are taxi drivers or work in warehouses that are inaccessible by bike – but otherwise pollute little. On the other hand, there are the well-to-do young people who are anti-car but who are fuelling the latest trend of wood burning stoves, which are extremely harmful to the air.

But, Phelps points out, it is the white middle and upper classes that are setting the environmental agenda. “The measures prioritised are the banning of polluting vehicles such as vans, and the development of cycle paths. No one is thinking of banning wood burning stoves or developing a network of affordable buses that fit in with factory hours.”

To involve Bristol residents in the fight against dirty air, RADE Bristol has set up a citizen air pollution measurement network, in partnership with several universities, the Council of Bristol Mosques and even the European Space Agency, which has provided a sensor. The data is collected and processed during introductory workshops in computer code and data visualisation organised for local children. They then relay the results to their families. In this street art city, artists have painted a mural to raise awareness of the health issues surrounding pollution. One of these painters, Aumairah Hassan, has co-created Cycling Sisters, a group that helps women, particularly those facing cultural or religious barriers, learn how to cycle.

These projects should gain real political traction with their inclusion in two neighbourhood forums, citizens’ organisations that local authorities have to consult regarding planning. At a national level, Boris Johnson’s government is also completing a consultation with researchers and citizens on how to tackle inequalities in its new clean air strategy. For Barnes, if not a revolution, it is a sign of growing awareness.