This 3 August 2023 photograph shows some of the 266 migrants rescued by members of the Spanish NGO Proactiva Open Arms after attempting to cross the Mediterranean sea on small boats off the Libyan coast. The Central Mediterranean route is currently one of the deadliest irregular migration routes in the world, with over 20,000 deaths recorded since 2014 according to the UN Human Rights Office.

With all the coups and wildfires, the cost-of-living crisis, the lingering-impact-of-Covid crisis, the rampant inequality crisis, the gratuitous, violent deaths of people on the move, the warnings of the existential risks posed by artificial intelligence, not to mention the looming catastrophe of climate breakdown and biodiversity loss, these must surely be the interesting times that the Chinese have been falsely attributed with wishing upon us. There are almost four times as many armed conflicts taking place today as there were in 2010, and while thousands continue to die in long-forgotten hostilities in places like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Yemen and the Central African Republic, the possibility of World War Three – thanks to rising tensions between China and the US and the ongoing war in Ukraine – remains in terrifyingly sharp focus.

Outside of the traditional theatre of war, grave human rights violations are proliferating from Palestine to Xinjiang. “Key measures of violations of workers’ rights have reached record highs,” according to the latest ITUC Global Rights Index, while civic space continues to shrink, and the rollback of LGBTQI+ rights, women’s rights and the rights of minoritised and racialised people continues apace. No region is untouched by this worrying momentum, although the expressions vary. In Europe it’s marked by far-right populism, nationalism and deadly, militarised borders; in many parts of West and East Africa, it looks like terrorist insurgencies and military coups; in the Americas, political violence and social unrest are a common theme; while, in the Middle East, the regional rehabilitation of Bashar Al-Assad and the rise of Saudi Arabia on the world stage exemplify the final, withered leaves falling off the hope that flowered during the ‘Arab Spring’.

Still, 2023 is a pivotal year for human rights. It marks the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a landmark, post-Second World War commitment adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in December 1948 to the fundamental human rights and freedoms that should be guaranteed for everyone, everywhere, and at all times. It was always an aspiration, but we seem to be in a moment where the asterisked exceptions to who this Declaration applies and under which circumstances is growing longer by the day. As a result, this year marks a crossroads: either world leaders will recommit to doubling down on the principles enshrined by the Declaration or they will eventually end up abandoning it altogether.

But while this selection of articles recently published by Equal Times highlights some alarming examples of human rights violations – the dismantling of democracy in Tunisia, the attacks on journalists in the most dangerous country to practice the trade (Cameroon), the price paid by people and the environment for constructing new capital cities, the use of mass surveillance in mass sporting events and the mounting death toll at the feet of Fortress Europe – each story also showcases the people, communities and institutions standing up to fight for something better. These examples show us that no matter how grave the threat, each one of us can still – and quite honestly, must try to – make a positive difference to our lives and those of future generations. However, any action must be underpinned by the understanding that our joint salvation is impossible without acknowledging and committing to the fact that all human rights are for all people. As the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk succinctly reminded us earlier this year: “The dignity and worth of every human being should not be – cannot be – a questionable, sensitive concept.”

On the brink of bankruptcy, Tunisia is sliding into populist autocracy

By Ricard González

Demonstrations against the Tunisian president Kais Saied last summer in the capital city, Tunis. Their banners remind us that “a people united” can never be defeated.

Just three years ago, Tunisia was celebrated as the only success story born out of the Arab Spring. However, beneath the glossy surface of its democratic institutions, growing unrest simmered over the failure to deliver on the promises of prosperity made during the 2011 revolution. Kais Saied, an independent politician with a reputation for integrity, was elected president in 2019 with more than 70 per cent of the vote. While some warned of the dangers of his brand of populism at the time, no one expected such a rapid and total descent into an autocracy with racist overtones.

Read the full article on Equal Times.

New capital cities, deforestation and social apartheid: the parallels between Brazil and Indonesia

By World Rainforest Movement

This screengrab taken from aerial video footage taken in on 14 August 14 2022 shows Titik Nol Nusantara (Ground Zero Nusantara), the future capital city for Indonesia, in Sepaku, Penajam Paser Utara, East Kalimantan. Located in eastern Borneo, Nusantara is set to replace sinking and polluted Jakarta as Indonesia’s political centre by late 2024.

[…] A striking parallel between both stories of the new capital cities is how both projects only reinforce a colonial state, in spite of their promoters claiming the opposite. Both projects dominate and destroy the life spaces and territories of forest communities for economic and political interests. And both new capital cities also promote policies of social apartheid.

Both stories, however, also show the role of social struggles as a way to put a halt to and revert a history of colonialism and other structural oppressions that include racism, capitalism and patriarchy.

Read the full article on Equal Times

In the name of security, France plans to monitor crowds using AI and algorithms during the Paris Olympics

By Clément Gibon

VIGI360 cameras provide 360° coverage of an area while recording images on a loop for a period of 72 hours. The technology can also be integrated into new intelligent video systems.

From the installation of 15,000 biometric cameras in Doha to surveil the behaviour of football fans during at the 2022 World Cup, to Iran’s introduction last April of cameras in public spaces to identify and punish women not wearing a hijab, to Israel’s use of facial recognition to monitor Palestinians in Hebron and East Jerusalem, governments are increasingly using mass surveillance technology to support law enforcement for security purposes.

Even countries previously considered to be more respectful of civil liberties are increasingly adopting new surveillance systems. In March 2023, for example, France opened the door to the experimental use of a controversial new technology when it voted on an article of the proposed law on the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games. This article authorises experimentation with algorithmic and automated video surveillance (AVS) at all sporting, recreational and cultural events with more than 300 participants until 31 March 2025. The law was promulgated on 19 May 2023 and the experimentation can thus begin.

Read the full article on Equal Times

Media workers in Cameroon face rising, violent repression; the murder of journalists is Exhibit A

By Amindeh Blaise Atabong

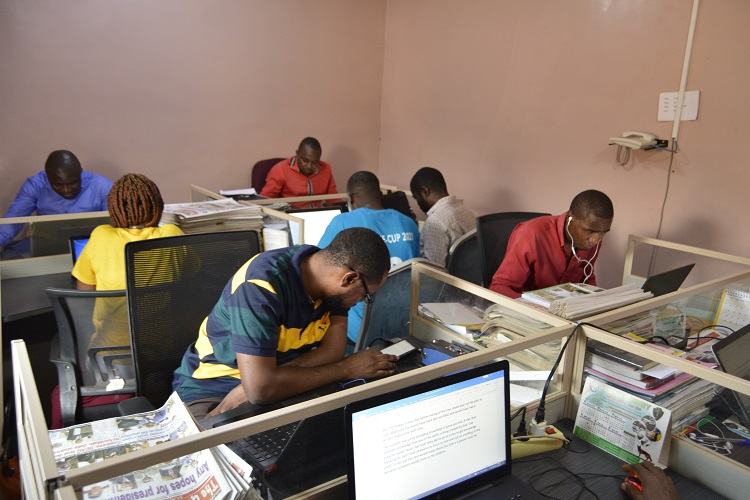

Editorial staff of The Guardian Post, Cameroon’s leading English-language daily, work on the next day’s newspaper at the head office in Yaounde, on 30 March 2023. The Guardian Post has suffered at least two separate months-long suspensions by the National Communication Council whose members are all appointed by President Paul Biya.

[…]Media freedom and journalist safety in Cameroon has been in decline over the last decade. This is because the government’s fight against Islamist insurgents Boko Haram in the north of the country and the protracted conflict between majority French-speaking government forces and Anglophone separatists in the Southwest and Northwest regions has resulted in journalists being under siege on several fronts.

Reporters Without Borders classifies Cameroon as having one of the most dangerous media landscapes on the African continent, marked by hostility and precariousness, while the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has found the central African nation, which has been ruled by its 90-year-old president Paul Biya since 1982, to be amongst the worst jailers of journalists in Africa.

Media workers are routinely attacked, threatened, censored, and imprisoned on anti-state, criminal defamation, false news, and/or retaliatory charges, as documented by the CPJ. Several journalists have been forced to go on exile.

Read the full article on Equal Times

How Europe’s broken legal migration system produces its border crises

By Farhad Mirza

This photograph taken on 9 March 2023, shows a view of a bamboo cross with a rosary, set as a memorial on a beach near Cutro, with the Mediterranean Sea in the background, where at least 72 migrants died on 26 February, after their boat sank off Italy’s southern Calabria region.

[...] Europe tells migrants to respect its border; to respect its laws, but it flouts its own laws when it comes to enforcing the border. Illegal and violent pushbacks of migrants have become a common institutional practice in the European Union, depriving migrants of the rights enshrined in European laws. Meanwhile, the human cost of such policies has produced a horrifying tally: almost 27,000 people have drowned in the Mediterranean since 2014. The shady deals with ‘safe transit countries’ to nip irregular movement in the bud have resulted in the emergence of migrant slave markets in Libya. The policy of illegal pushbacks has led to massacres such as the one in Melilla in June 2022 when a group of African asylum seekers attempted to cross from Morocco into the Spanish enclave and were met with deadly violence by security forces, leaving between 23 and 37 people dead. No one has ever been held accountable for these deaths.

The West keeps shifting the blame for these failures on smugglers and dodgy economic migrants but it is time it reckoned with its active role in shaping this murderous landscape. Discourses of illegality, security and legitimacy obscure the shortcomings of ‘legal’ immigration and the reasons why so many people in desperate conditions are left with no other option but to take illegal routes.