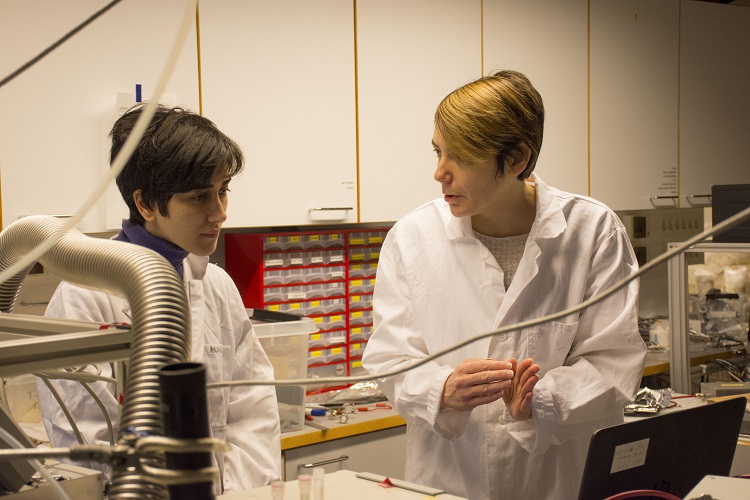

Monica Passananti (left), postdoctoral fellow in physics, and Golnaz Roudsari (right), a PhD student in theoretical physics, at the Atmospheric Mass Spectrometry & Atmospheric Physical Chemistry Laboratory of the Physics Department of Helsinki University.

Why do so few women opt for or complete science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) degrees, occupy less than two out of every 10 jobs and represent 22 per cent of the female graduates in these sectors in the European Union? And even more importantly, what can be done to end this underrepresentation, bearing in mind that STEM studies are particularly challenging and therefore less attractive to men and women alike, despite being the most promising in terms of the job opportunities provided by the Fourth Industrial Revolution in which we are currently immersed?

Gender segregation, both in the world of education and work, be it vertical (the concentration of one gender within certain pay scales, levels of responsibility or posts) or horizontal (the concentration of one gender in certain fields, men mainly in STEM, and women in education, health and welfare, to the tune of over 60 per cent), is a reality across the EU. The segregation in STEM, education, health and welfare sectors, where the highest levels exist, has seen no improvement in the last decade, and remains “persistently high”, according to the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE).

In its report on gender segregation in education, training and the labour market, drawn up for the Council in October 2017, the EIGE is emphatic: “Gender segregation narrows life choices, education and employment options, leads to unequal pay, further reinforces gender stereotypes, and limits access to certain jobs while also perpetuating unequal gender power relations in the public and private spheres,” and is one of the factors contributing to the shortage of STEM professionals, as well as to the inefficiency and rigidity of the labour market.

The Gender Equality Index published in October 2017 by the EIGE reveals that, “Women usually take jobs in sectors that are generally characterised by low pay, low status, low value, poor career prospects, fewer options for upskilling and often with informal working arrangements. The concentration of women and men in different sectors and occupations is a major cause of the gender pay gap, the gender gap in pensions and women’s overall economic dependence throughout their life.”

In addition, the World Economic Forum warns that: “The slow rate of progress towards gender parity, especially in the economic realm, poses a particular risk, given the fact that many jobs that employ a majority of women are likely to be hit proportionately hardest by the coming age of technological disruption known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution.”

It comes as little surprise that this segregation is reflected in the Nobel prizes. Since 1901, only 48 out of the 923 laureates (including 27 organisations) have been women (with 49 awards - Marie Curie was given two); sixteen of them received the Nobel Prize for Peace, 14 for Literature and 12 for Medicine. As for the prestigious research funds awarded by the European Research Council (ERC, which has taken measures not to penalise motherhood), the proportion of Advanced Grants awarded to female investigators in 2017 was 16 per cent, and the proportion of Consolidator Grants was 32 per cent.

Scientific method and human rights

There are various arguments that could be used to demolish the obstacles and the contempt suffered by women in STEM fields throughout history – from the astronomers Maria Kirch and Mina Fleming to the first programmer Ada Lovelace and the mathematician Emmy Noether or the chemist Rosalind Franklin. Specific obstacles such as the glass ceiling, sticky floor, implicit bias, or the gender pay gap add to the difficulty of these disciplines and prevent women from all over the world from swelling the ranks of STEM students, or from staying the course, a phenomenon known as the “leaky talent pipeline”.

The most obvious of these arguments is the scientific method summarised by astrophysicist and science reporter Neil deGrasse Tyson as: “Do whatever it takes to avoid fooling yourself into thinking something is true that is not, or that something is not true that is.”

Although studies debunk preconceived ideas such as ‘the underrepresentation of women in STEM studies will resolve itself naturally over time’, ‘academia is a meritocratic environment’ or ‘the women in these fields are less productive are less competitive than their male counterparts’, it would seem that the scientific and technological world is rather slow off the mark when it comes to recognising the data available – which ultimately points to a problem of gender-based segregation and discrimination.

Nor is the human rights argument seemingly capable of tackling the problem (in fact, more subtle forms of sexism, which have arisen recently in Germany, France, Hungary, Poland or Slovakia, are amplifying the latent threats to gender equality, according to the EU Fundamental Rights Agency, also known as FRA).

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union prohibits all forms of discrimination based on sex and establishes that “equality between women and men must be ensured in all areas, including employment, work and pay”.

The FRA also points out in its paper Challenges to women’s human rights in the EU that, “If violations of these rights are left unchecked, the EU and its Member States risk not meeting their objectives of achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls by 2030,” in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which include eliminating discrimination, violence and harmful practices against women and girls, and enabling their full participation in political, economical and public life.

“Pervasive gender stereotyping prevents women and girls from fully enjoying their rights and entrenches structural aspects of gender inequality,” summarises the FRA.

According to the EU agency, women are confronted with pervasive structural gender inequality in the world of work. In a survey conducted in 2012, the FRA found that 14 per cent of women had experienced some form of gender-based discrimination at work at some point during their life. The higher the level of studies, the greater the perceived sense of discrimination: 22 per cent in the case of women with a university education. The figure rises to 28 per cent among women in senior management positions.

“Although the legislation protects me, the fact is that (as a mother and a scientist), I have to juggle. This little realm is a men’s club, and the men tend to support other men. The more you are part of the men’s club the more opportunities you get. In other words, you have to become one of the men, and that’s what I have done. I hate it, because it goes against the basic principle of equality. But that’s the way it is, your knowledge is not what matters the most. In this society [Dutch], it is the woman who is expected to take the time to look after the children. I would like to be judged on my scientific knowledge, not on the basis of being a ‘woman’, a ‘mother’, or a ‘wife’, and if that is the basis for judgement, then I should be considered as a person with 10 jobs,” says a postdoctoral fellow in molecular biology, virology and immunology from the former Yugoslavia who completed her studies in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, where she is currently working.

Europe, in theory, has the most enabling environment for women when it comes to working in science, technology, engineering and maths related jobs. Although there are major differences between the different countries, overall, Europe comes first in the World Economic Forum’s ranking on closing the gender gap (which assesses four areas: educational attainment, health and survival, economic opportunity and political empowerment, in a total of 144 countries).

According to the WEF, western Europe is the frontrunner in the narrowing of the gender gap, with Iceland, Norway, Finland and Sweden holding four of the top five places.

The EU has various initiatives aimed at eradicating gender-based segregation in education, training and the labour market: the most recent is the European Pillar of Social Rights. Other examples include the Strategic Framework for Education and Training 2020 (ET 2020), the Europe 2020 strategy for jobs and smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, the EU’s Strategic Engagement for Gender Equality 2016-2019, which identifies equal economic independence for women and men as a priority area, as well as the EU’s commitment to the UN Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA).

At national level, not only has there been legislation on equal pay for over three decades, for example, but many governments have adopted a variety of measures over the past decade to try to close the gap, ranging from gender mainstreaming in national legislation, agreements with social actors, equality plans, awareness raising, etc. In the United Kingdom, for example, mandatory pay gap reporting was introduced in April 2017 for all companies with over 250 employees.

But very little is being achieved in practice, be at state or EU level: “So far, EU policies aimed at reducing gender segregation are not reversing the trend or are having little impact. More action and more implementation is needed,” summarised the EIGE researcher and analyst, Jolanta Reingarde, at a seminar in the European Parliament in March 2017.

Finland, an (incomplete, non self-complacent) example to follow

“In some senses, in Finland, women are appreciated as a workforce. It is a small country [5.5 million inhabitants] that has suffered terrible wars. Everyone has had to work hard to rebuild the economy, both men and women. We don’t have gold or a mining industry, and on top of that, we have the climate we have,” physics professor Hanna Vehkamäki, tells Equal Times, on a typical frozen morning in Helsinki at the end of December.

“It is possible [for a couple] to have children and a career without being millionaires and without one of them having to leave their job. There are good laws in terms of maternity and paternity leave and childcare facilities are affordable,” explains Vehkamäki, highlighting some of strengths of this Nordic country that prides itself on having been the first in the world to recognise the right of women to stand for election, and the first in Europe to recognise their right to vote (both in 1906), and on having committed to gender equality as a fundamental national value.

Not only is it not a huge strain on the wallet, but nor is motherhood penalised when it comes to assigning projects, posts or funding, points out the vice rector of the University of Helsinki, Pertti Panula. “In addition to the applicants’ merits – which is always the chief consideration – the number of children they have is taken into account when an age limit is set.” Women applicants benefit from positive discrimination and the age limit for a post is raised according to the number of children the applicant has.

“The structural problem [of sex discrimination or the penalisation of motherhood, for example], has been almost totally overcome in Finland. But there are many little things that are unconsciously said or done, and that hold women back in their careers. I’ll give you an example that I witnessed: when presenting a study conducted by three scientists, two men and a woman (more qualified, if anything, than them), the two men were referred to as ‘experts’ and the woman was introduced as ‘experienced in’..., which is not the same, and the consequences of this are seen in the long run,” explains Vehkamäki.

One of the reasons this change is “going to be painstakingly slow”, the physicist points out, is that men are often oblivious to the problem. Data from 2012, shown within the framework of the equality festival held at the Kumpula campus of Helsinki University in December 2017, speak volumes.

For example, to the question “Is the physics department managed in an equitable manner?”, 41.5 per cent of the male employees answered “yes” compared with 16 per cent of their female colleagues.

The vice rector of Helsinki University insists that the institution is equipped with mechanisms to enable women who feel discriminated against or who suffer harassment to report it directly, and mechanisms to ensure that suitable measures are taken. He also underlines that the academic institution he represents prioritises gender equality (which is second only to academic excellence), and one of the results, for example, is near parity in the number of male and female rectors in its 11 faculties: six male rectors and five female (whilst the overall proportion of female rectors in Europe is around 20 per cent).

When redundancies have to be made, as was the case in 2016, due to funding cuts, a balance is ensured in terms of gender. “The trade unions did not welcome the staff cuts, but they encountered no problems in terms of gender disparity.”

The gender equality unit of the Health and Social Affairs Ministry does not consider the task to be complete. It is continuing to work on challenges such as the gender pay gap, gender stereotypes and segregation in education and the labour market. “The changes are very slow, but the government is exploring new measures”, such as increasing the number of days of paternity leave, or raising and levelling out the maths requirements for all students, regardless of the fields they choose, explains ministerial advisor Riitta Martikainen.

When the winning argument is economic

“Improving gender equality will help to address employment, productivity and population ageing issues,” argues the EIGE in its study on the Economic benefits of gender equality in the EU.

The EU body underlines that most member states have experienced “severe recruitment difficulties in relation to STEM skilled labour, especially in engineering and IT […]. For instance, in the United Kingdom more than 40 per cent of job vacancies (double the country’s average) in STEM have been hard to fill due to a shortage of applicants.” It should not be forgotten that an eight per cent increase is forecast in the demand for STEM professionals by 2025.

In relation to concrete forecasts, according to the EIGE study, “If gender equality is substantially improved by 2050, the EU employment rate will reach almost 80 per cent compared to 76 per cent in the absence of substantial improvements [tackling gender segregation in academic choices and increasing women’s participation in STEM studies]. By the year 2030, the employment rate in the EU will reach 72.6 per cent. There will be between 6.3 and 10.5 million additional jobs in 2050...and about 70 per cent of these jobs would be taken by women.”

With regards to GDP, the results of the EIGE study point to a potential increase of up to 2 per cent in the medium term (2030) and up to 10 per cent in the long term (2050), “leading to an increase in EU GDP per capita of 6.1 to 9.6 per cent, which amounts €1.95 to €3.15 trillion”.

The member states currently taking limited action in the area of gender equality have the most to gain from closing their gender gaps, that is, Belgium, Slovakia, Croatia, Lithuania, Italy, Czech Republic, Poland, Portugal, Greece and Bulgaria.

And in the case of STEM education alone, the European institute concludes that closing the gender gap in this area would contribute to an increase in EU employment of 850,000 to 1.2 million by 2050, would contribute to an increase in GDP per capita of between 0.7 per cent and 0.9 per cent by 2030 and between 2.2 per cent and 3 per cent by 2050; and would lead to a rise in GDP of between €610 billion and €820 billion in 2050.

Moreover, “a higher participation rate of women in science and technology-related areas would bring greater opportunities for more sustainable science and growth of the sustainable and ‘green’ economy.”

Till Alexander Leopold, project lead for education, gender and work at the World Economic Forum, tells Equal Times that although they have not calculated or endorsed the figures, they do use them: “There is no sensationalism, they are realistic.”

This forum, in fact, began calling for an acceleration in the drive for gender equality several years ago. In its white paper Accelerating Gender Parity in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, published last summer, it points out that to benefit from this new socioeconomic context and to navigate the uncertainties it brings, “all sectors need to increase diversity within their talent pools and their leadership to benefit from the range of perspectives, creative thinking and skills needed”. And “the current moment thus offers a strategic win-win opportunity to proactively enhance gender equality and prevent widening gender – and skills – gaps”.

The Forum’s call for urgent action was prompted, in addition, by the poor results observed overall in its latest study on the closing of the gender gap. According to the estimates (not “inevitable outcomes”), the gender gap in the world of work will not be closed for another 217 years, although western Europe (in addition to Slovenia, Bulgaria and Latvia) “remains the highest-performing region in the Index, with an average remaining gender gap of 25 per cent”.

Klaus Schwab, executive chair and founder of the WEF is categorical: “Competitiveness on a national and on a business level will be decided more than ever before by the innovative capacity of a country or a company. Those will succeed best who understand to integrate women as an important force into their talent pool.”

… but first some groundwork needs to be done

To materialise the positive impact on employment, GDP, dynamism and sustainability, one of the main causes of gender inequality needs to be addressed: the unequal distribution of unpaid care and family responsibilities, as highlighted by the EIGE, which underlines the need for concrete measures such as better access to affordable, good quality childcare, family-friendly and flexible working arrangements, the promotion of more equal take up of flexible working schemes by both men and women, and the promotion of women to managerial posts.

With regards to measures to increase the number of female graduates in STEM sectors, the European institute – along with the World Economic Forum – insists on eradicating gender stereotypes in education, raising awareness and promoting STEM subjects among girls and women, and providing career advice that encourages girls to study in fields dominated by men, and boys to study in fields dominated by women.

“Getting the girls closer to STEM subjects is very important. It needs to happen very early – in pre-school or school,” insisted Petra Jantzer, managing director and the European lead for Accenture’s Accelerated R&D Services (ARDS), at the STEM Equality Congress in Berlin, in June 2017.

At company level, UNESCO’s Science, Technology and Gender: An International Report, from 2007, underlines that, “Some employers simply refuse to employ women in professional S&T roles. Women can also be made to feel very unwelcome in certain working environments. This may be deliberate, or it may be an unintended effect of a ‘macho’ culture within the organization. Sexual harassment affects the working life of many women, even though it is hard to quantify. To benefit from more women in the S&T workforce, it is essential to address any aspect of company culture that allows such abuse.”

For Irene Rosales, policy and campaigns officer for the European Women’s Lobby, there is no doubt: Women in “male dominated sectors like STEM or the tech sector are at a higher risk of facing harassment and sexual harassment. Male dominated sectors create spaces where women’s voices, stories and personas are alien.” And as underlined by Marianne Bruun, equality advisor for the Danish trade union 3F, in the ETUC report Safe at Home, Safe at Work: “Sexual harassment is about power – rarely about sex, more often about power. This is what we need to address if we want to tackle sexual harassment.”

Siân Webb, manager at the British company Gapsquare – a tech company that has developed leading-edge software designed to close the gender gap in companies – explains that the pay gap, which continues to increase, is not only a deterrent for women entering STEM but also contributes to the leaky pipeline. In addition, the STEM sector “supports and promotes the full-time employee”.

“We need competitiveness, but perhaps a less ‘brutally competitive’ culture. There is admiration for long working days, addiction to work, to giving everything up for your career, it’s like a myth. And we forget that we need to rest, because if we don’t, creativity suffers and so do the results. A change in culture is essential, and not only for women,” says Vehkamäki.

“This is not just a woman’s issue,” Webb agrees, “Men in STEM who are also trying to work part-time, flexibly or against this out-dated model of working find themselves under too much internal pressure and realise it will jeopardise their careers and promotional opportunities.”

Be it for humanitarian, scientific or materialistic reasons, the need to put an end to inequality and gender segregation is not only imperative, it is the only way forward. As Markus Nordberg, head of resources development at the CERN, sums up: “Think big, do good.”