In 2016, more than 1.9 billion adults (39 per cent of the global population) were overweight, of which over 650 million were obese. According to data from the World Health Organization, in the space of just 45 years, worldwide obesity has nearly tripled

Out of all the countries of the world, Mexico ranks first in the world in childhood obesity and second in adult obesity. According to the country’s 2018 National Health and Nutrition Survey, 75 per cent of Mexicans aged 20 and over are overweight or obese. Even more alarming, 35.6 per cent of the country’s children aged 5 to 11 are overweight or obese.

The trend toward overweight and obesity among Mexico’s ‘Generation Alpha’ and part of its ‘Generation Z’ is cause for serious concern. The obesity epidemic is a health problem that concerns everyone, not just people who are overweight.

A parallel increase in chronic non-communicable diseases associated with obesity, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, has also been detected. And with the coronavirus pandemic yet to be brought under control, both overweight and obesity pose greater risks for those who become infected with Covid-19.

According to Mexico’s Secretariat of Health, in addition to “poor school performance and emotional problems such as diminished self-esteem,” these diseases not only cause problems for people who suffer from them, but also for the country’s economy: “The OECD estimates that Mexico’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will decline by 5.3 per cent between 2020 and 2050 due to the epidemic of overweight and obesity, which also negatively impacts vulnerable groups.”

According to the Health Secretariat’s calculations, the total cost of obesity in 2017 alone amounted to 240 billion pesos (€9.9 billion, US$12 billion), an amount predicted to rise to 272 billion pesos (€11.2 billion, US$13.6 billion) by 2023.

A quick glance inside any shop in Mexico will reveal the high number of processed foods on offer.

Until recently, studies addressing the causes of obesity have focused on the poor choices made by individuals, but have rarely looked at the obesogenic environment, which the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) describes as “an environment that influences personal preferences to consume food products high in calories, simple sugars, fat and salt, and low in nutritional quality.”

The Alianza por la Salud Alimentaria (Food Health Alliance), a group of organisations made up of academic experts and food rights activists, identifies as main factors “the accelerated deterioration of the population’s eating habits,” specifically a “decrease in the consumption of fruits and vegetables, cereals and legumes that belong to the traditional Mexican diet, which is rich and balanced, based on the cultural and biological diversity of the national territory, and centred on the milpa system of cultivation.”

Sourcing local, fresh and reasonably priced products has become more difficult than sourcing junk food.

“Instead, we have seen an increase in the consumption of refined flours, sugary drinks, ultra-processed foods and beverages, supported by the large-scale marketing campaigns that dominate physical and virtual space due to insufficient regulation,” says the Alliance.

“This epidemic is the result of an epidemiological transition that began in the 1980s and continued throughout the 1990s and 2000s. It entailed changes to the food system and to trade, as well as lacking regulation of very aggressive commercial practices when these changes began to take shape,” said Simón Barquera Cervera, director of the Centre for Health Research (CINS) of the National Institute of Public Health (INSP), at a press conference on 20 August 2020.

Amaranth seed-based snacks like the ones pictured here are a part of the traditional Mexican diet. They are being displaced by snacks produced by a variety of agri-food multinationals.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), signed between Mexico, the United States and Canada in 1994, and the arrival of large fast food chains “was a watershed moment. These highly processed products were suddenly available, cheap and had great publicity, which encouraged people to purchase them,” Paulina Magaña, coordinator of the food health campaign of El Poder del Consumidor (Consumer Power), tells Equal Times.

In January 2014, the Mexican government implemented a sugary drinks tax of one peso per litre (approximately 10 per cent). By the end of that same year, the consumption of sugary drinks had dropped by 12 per cent, while the consumption of unsweetened beverages such as bottled water increased by 4 per cent.

Elaborate marketing campaigns by the agri-food industry are fuelling new habits of consumption.

According to the INSP, applying the tax over 10 years would result in savings of approximately US$91.6 million in health care spending and prevent almost 240,000 cases of obesity, more than 61,000 cases of diabetes, almost 4,000 cerebral vascular events, more than 2,800 cases of hypertensive heart disease and more than 4,000 cases of ischaemic heart disease.

“Mexico’s 10 per cent tax doesn’t go far enough. We’ve learned from the experiences of other countries, the United States for example, where some cities have a tax of 30 per cent and have seen a 38 per cent reduction in the consumption of sugary beverages. Our organisation’s objective is to double the current tax,” explains Magaña.

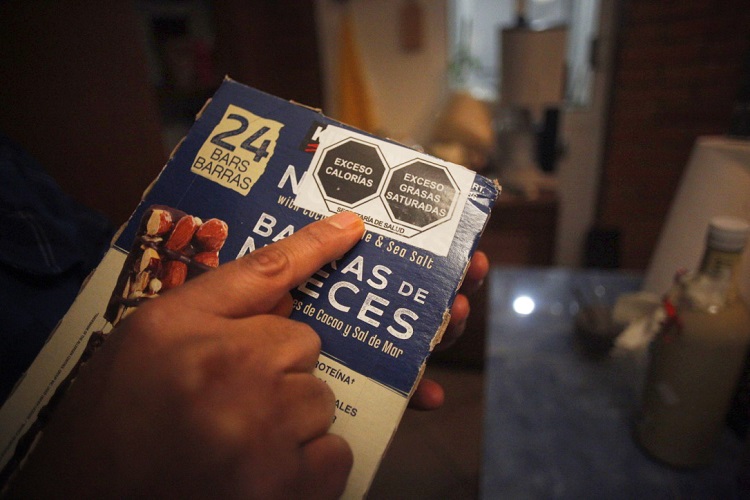

Another strategy for combatting the overweight epidemic is front-of-package labelling, recently adopted by Mexico. Following a multi-year campaign spearheaded by the Alliance for Food Health, the Official Mexican Standard NOM-051 came into force on 1 October 2020. It requires front-of-package labelling for food and non-alcoholic beverages that provides consumers with a truthful and concise warning of excess sugar, saturated fats, sodium and other critical nutrients and ingredients. The previous system of labelling was not clear to consumers as it displayed the proportion of ingredients per portion as a percentage of the recommended daily allowance.

Implemented in 2020, front-of-package labelling now provides a clear and concise warning about the amount of excess sugars, saturated fats and other ingredients.

In the new system, based on the PAHO Nutrient Profile Model, products receive up to five labels for excess sugars, saturated fats, trans fats, sodium and calories.

“Information is power, and as consumers we didn’t have accurate and clear information that could help us make decisions. This labelling system now gives us the ability to decide what we consume, it helps us to demystify products. We are beginning to realize that many products that we previously consumed because we thought them to be healthier for us are in fact not,” explains Diana Delgadillo, public policy advocacy manager at The Hunger Project (THP) Mexico.

In the state of Guerrero, located next to the state of Oaxaca, several communities grow and consume products that originate from the area.

Beyond taxes and front-of-package labelling, the greatest challenge facing healthy eating advocates is how to bring healthy food to both rural and urban areas.

“According to FAO data, it is five times more expensive to access a healthy diet than a diet based on ultra-processed foods. And while Latin America is the most expensive in this regard, all over the world it is more expensive to access a healthy diet than an ultra-processed diet,” says Delgadillo, who points out that the right to adequate food “is guaranteed by the United Nations.”

At fault, he argues, is a multifaceted profit-based food system. According to Delgadillo, a possible solution lies in “moving towards a food system where different diets, cultures, ecosystems and territorial contexts coexist, where food is seen as a right rather than a commodity.”

In the state of Guerrero, located next to the state of Oaxaca, several communities grow and consume products that originate from the area.

The Plato del Buen Comer Mazateco, a project by THP Mexico in partnership with members of the community of San José Tenango, Oaxaca, is an example of how to achieve healthy and nutritious food in a region with high rates of malnutrition, marginalisation and poverty. The initiative has, among other things, rescued seeds native to the region, analysed the nutritional value of local crops, and encouraged the development of small gardens and the commercialisation and consumption of local foods shared in the community, without the need to travel kilometres to obtain them.

According to Maribel Gallardo, regional coordinator of the THP Oaxaca office, the community began to record and compare the illnesses from which their ancestors suffered to those they suffer from today, and look for ways to improve their health.

“The community organised itself, we began to talk with our grandparents about the foods we used to eat, the foods we no longer eat and the foods we didn’t even know existed, as well as how those foods are prepared. There were recipes that I didn’t know about that differ from community to community.” As Gallardo explains, the project encouraged dialogue between different communities, which allowed all of them to discover different flavours.

“We now prefer making our own soup to going to the shop to buy a ready-made soup. We are rediscovering traditional products.” The economic impact on the community has also been positive: the cost of a single item that comes from outside of the community (an individual container of yoghurt, for example, which costs 10 pesos), can buy enough chayote to feed an entire family.

But spreading the benefits of initiatives such as the Plato Mazateco as a way of addressing the obesity epidemic will require the involvement of health authorities and an articulated strategy at the national level.

As Delgadillo emphasises, the processes of rediscovering local food, decreasing the distances that food travels, and establishing food sovereignty focus on creating true value rather than generating profit: “The use value of food rather than its exchange value.”