A ceremonial mask presented to the Democratic Republic of Congo by King Philippe of Belgium, during a ceremony at the National Museum of the Democratic Republic of Congo in Kinshasa on 8 June 2022.

In September 2023, one year after the launch of the PROCHE project, Bart Ouvry, director of the AfricaMuseum, the former colonial museum built by Leopold II near Brussels, travelled to Kinshasa to strengthen cooperation and cultural exchange programmes between the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Belgium.

Led by Célia Charkaoui, PROCHE is a project looking into the origins of the works and objects currently in the museum’s collections, the vast majority of which come from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Plundered by Belgian colonialists, these collections bear witness to a violent colonial past. Today, they could not only provide fertile ground for reconstructing history but also for reparation between the two countries.

This new cooperation is part of a wider series of programmes launched by a number of European institutions, in France, the Netherlands and elsewhere, in response to requests from the countries colonised.

Restitution: what is at stake for the DRC?

Although Belgium’s colonial rule of the DRC officially ended in 1960, when it gained independence, the country’s colonial history and its impact are as topical today as ever. In November 2022, the Congolese minister of culture, Catherine Kathungu Furaha, presented a decree, which has since been approved, calling for the repatriation of the goods, archives and human remains still owned by Belgium, the vast majority of which are in the collections of the AfricaMuseum.

The decree has led to the establishment of a national commission for the repatriation of these items, as well as more intensive exchanges between the National Museum of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Kinshasa and the AfricaMuseum. A future bilateral agreement between the DRC and Belgium is also being discussed.

While the repatriation of goods stolen during the colonial period is a key issue, the word ‘restitution’ in the DRC refers to a much broader concept. The term refers more readily to a long process involving not only the reconstruction of history but also the reconstitution of knowledge, particularly among local Congolese communities.

Five researchers are currently working in the archives of the AfricaMuseum as part of the PROCHE programme, for a period of three months, to gather information enabling the history of the objects to be retraced, so that they can be handed over to the families, villages and communities to whom they belong.

As Augustin Bikalé, head of communications for UNESCO’s cultural department in Kinshasa, explains, it remains to be seen, or determined, rather, which objects will be returned and what impact this repatriation will have on the stability of communities.

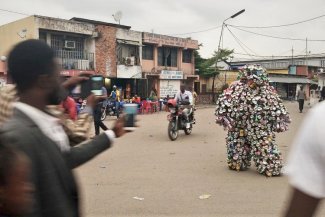

The example of the Suku Kakuungu mask, currently on display at the Kinshasa museum as part of an indefinite loan from Belgium, shows that the choice of objects and the framework for their restitution should come from the DRC.

Placide Mumbembele, a professor at the University of Kinshasa and a specialist in restitution issues, explains that this loan, and the tensions it has reignited between certain communities, illustrate the extent to which the exchanges are still very unilateral. He suggests that this should be redressed, not only by including local Congolese communities in the discussions, but also by starting with the repatriation of one symbolic object per province, which amounts to 26 objects in all, as soon as possible.

More than just a physical transfer of looted objects, it is a matter of governance. For instance, an immediate symbolic transfer of ownership would reverse the balance of power, as the DRC would be lending the objects to Belgium, rather than the other way round.

Decolonisation in the spotlight

The law passed in Belgium in June 2022, recognising “the alienable nature of property linked to the colonial past of the Belgian state and establishing a legal framework for its restitution and return”, together with the Belgian King’s visit to Kinshasa, is viewed in the DRC as inadequate, and even as evidence of North-South relations still based on an unequal balance of power. The fact that archives (photographs, diaries, etc.) and human remains are excluded from the Belgian law on restitution reveals a clear lack of cooperation.

In this regard, Placide Mumbembele notes that in Europe, “restitution is still presented as a transfer from North to South, whereas it should be a two-way flow, an exchange of goods and ideas”. He mentions ways of addressing this, such as holding scientific colloquiums on Congolese soil, so that knowledge can also be spread from South to North, as well as inter-museum loans, putting African and Western museums on an equal footing.

It may be hard, right now, to imagine a Belgian artist exhibiting at the National Museum of the Democratic Republic of Congo, but this is an interesting avenue to explore if we are to see the two countries working together on an equal footing.

Financing research and heritage conservation and preservation is another key issue, as highlighted by the scientific committee of the National Museums Institute of the Congo (IMNC). As Henry Bundjoko, director of the National Museum of the Democratic Republic of Congo, points out, “the expertise of the Congolese, through their knowledge of the terrain and communities, is crucial in filling the historical gaps left by colonisation”.

The focus must therefore be on open dialogue, with multiple voices, between Belgian and Congolese museums, between their scientific experts, and also between Congolese civil society and Belgium’s institutions, which must be prepared to listen to this plurality of views.

Long-term cooperation

Research into the origins of objects, access to archives and scientific work on the heritage that is still in Belgium are key to establishing equal and lasting relations; this work must therefore be assessed and implemented by Congolese researchers, who are in direct contact with the source communities.

With the launch of the SMART project at the AfricaMuseum, work is being done to promote “ethical management and the empowerment of museum and material heritage networks in the DRC”. The aim is to provide institutional support, through training, academic reinforcement and technical assistance, for Congolese museums and people in the cultural sector.

This collaborative project also seeks to raise awareness of these issues among the European public, because, as Augustin Bikalé points out, “restitution is a social issue that concerns everyone”. As the AfricaMuseum celebrates its 125th anniversary and its fifth year of reopening, workshops, conferences and exhibitions are being held on a regular basis.

As part of the provenance research, the history of the objects that have been analysed can now also be retraced, thanks to a small pink pictogram entitled “provenance”, which provides a complete history of the objects.

For Amzat Boukari Yabara, a Beninese-Martinican historian specialising in pan-Africanism, the initiative is essential. Museums, he says, “should not be art museums but history museums”, with an objective that is educational, not a fetishisation of exotic objects presented to Europeans.